Neil Varcoe was a tech executive in Sydney until he bought an old hotel in Carcoar, NSW, population 272. Here’s the 14th instalment of his monthly column for Galah.

Witness marks are the scars left behind by time. They are the fine scratches on a clock’s movement, the shadows, the screw holes on the case. They whisper secrets to antique clockmakers about previous repairs. They reveal the history of an object, not only by what has been added, but also by what has been taken away. These marks are also a blueprint of sorts, a map.

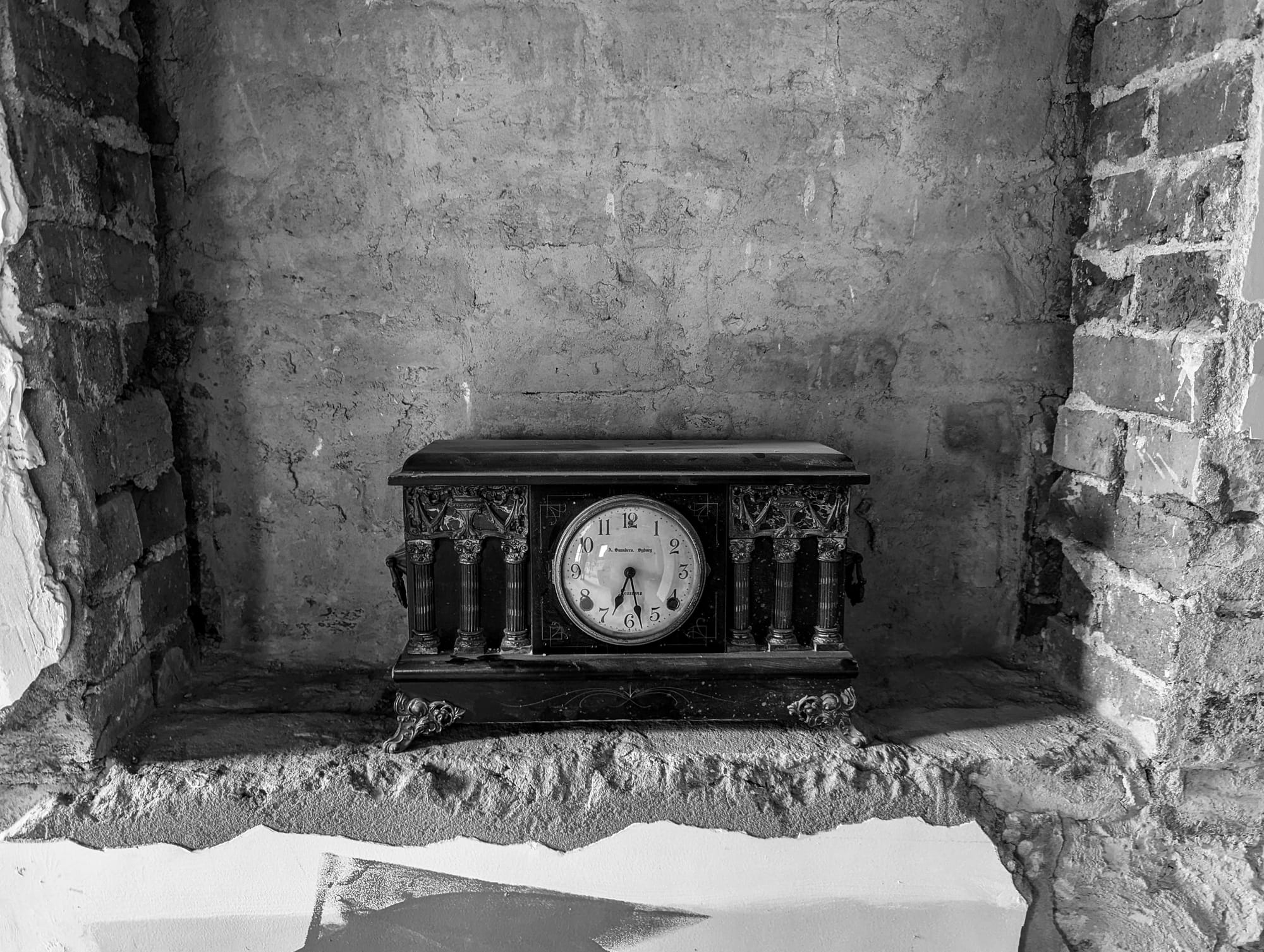

As the Saltash builders inspect the foundations to see how it was put together and altered, I find an old clock in the rubble, and start thinking about my own witness marks.

The antique clock sat elegantly by the fireplace, her face wide, her body tired. Molly was three and hung low in the crook of my arm like a bag of spuds. The owners, Phil and Ellen Cram, continued the tour. It was the first time we had been inside the first pub in town.

We walked through a door into a manager's apartment. This concluded the tour of the heritage building and began the inspection of the new additions. Molly turned to me: "Daddy, I'd like to live here one day," she said. An electric jolt ran through my body. "You will," I thought.

The Sessions mantel clock sat quietly on the other side of the wall. How many moments had it witnessed? How many lives had it seen changed?

My father lived in the house his father built, or so I thought. The man who likely constructed the double-brick house on a double block on Farmer's Creek in Lithgow was Charles Hoskins, an Australian industrialist and steelmaker.

My grandparents passed as my father entered adulthood, and he died when I was 16, so I don't know for sure. It's likely, though. The house stands proudly in the shadow of Lithgow Blast Furnace, where Hoskins established Australia's first commercial steel works. The house was not just close to the blast furnace and steelworks, it was typical of Hoskins — well-built and practical.

After acquiring the blast furnace and all other assets of Eskbank Ironworks from his friend William Sandford, Hoskins began a rapid and seismic upgrade of the blast furnace, ironworks and an iron ore mine at Coombing Park near Carcoar. When the long-term viability of the steel works was challenged by its distance from sea ports for iron ore and exports, Hoskins sold Coombing to Thomas Icely, the man who built Saltash Farm.

I have written about the sense of destiny in this project — how I feel in my blood, in my bones, that I'm supposed to be here. And I can't Google a clock without finding another link to this place.

I grew up in the house on Farmer’s Creek — the house my grandfather didn't build. Its central hall was a race track for four wild kids. In the lounge room sat a mantel clock — my grandmother's clock. It shook and rattled as we tore past. It was the tick-tock rhythm of the house.

My father ensured that it was wound, and the clock, in turn, kept the house running on time. My mother asked me if I wanted anything from the house when we bought Saltash Farm. I asked for the clock

The clock from the house that Hoskins built — my grandmother's clock — will witness countless moments at Saltash Farm that she never would. In the home her grandson built.

As I turn the clock key, I wonder if my father wound it to maintain a connection to his mother. As the hands start to turn, I can almost see his reflection in the glass. His crooked smile. Those bright, shining eyes. I feel close to him in this moment. It heals the scars. The witness marks.

RAG Status Reporting is used in project management to update executives quickly using a traffic light system. "Red" means trouble, "amber" signals bumps in the road, and "green" means everything is fine.

Please see the latest report below. Drill down on the data and help us square the circle.

The Project is On Track.