Epics require dedication and an empty diary. Does Sarah Gilbert have the stamina for the 500-plus pages of Carpentaria?

Words Sarah Gilbert

There’s nothing I like better than a great big saga. Some of my happiest and most memorable reading experiences involve very fat books – lying under the air-conditioner in my grandmother’s Riverina home one hot January, my mother feeding me sandwiches of leftover Christmas ham so I could remain there, undisturbed, as I devoured A Suitable Boy. Or my honours year, when I lived alone in a little college dorm and sat beneath the window with War and Peace for several hours a day.

Most of these reading memories belong to my early adulthood, when I had a lot more time. Or in windows of life when time seemed to slow down, or even stop: the bout of malaria I spent reading The Forsyte Saga, or Covid, when I re-read Middlemarch. And I’ll always associate the early weeks of my daughter’s life with Anna Karenina, which I propped against her well-swaddled bum as she slept in my arms.

These days, many of us feel there is just no time for that sort of reading, and we are too distracted – by domestic tasks or work demands that eat into our home time, by the endless easy offerings on TV and, most of all, by the phone. But what I have noticed on those relatively recent and very rare occasions when I’ve been sucked into a 500-plus-page adventure (Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels and Elizabeth Jane Howard’s Cazalet Chronicles come to mind) is that once I’m hooked, time seems to magically expand to meet my pressing need to stay in the story.

It’s an experience that gives me back the time I feel I’ve lost, as I happily neglect tasks that turn out to be almost absurdly unimportant, and I lose interest in screens.

But yes, it’s rare. My to-read bedside pile is mostly stacked with short fiction and essays – stuff I can feasibly get through in the tiny sliver of time between tucking myself into bed and falling, exhausted, into sleep. There is one book there, though, that has been staring at me for years – both a temptation and a silent recrimination.

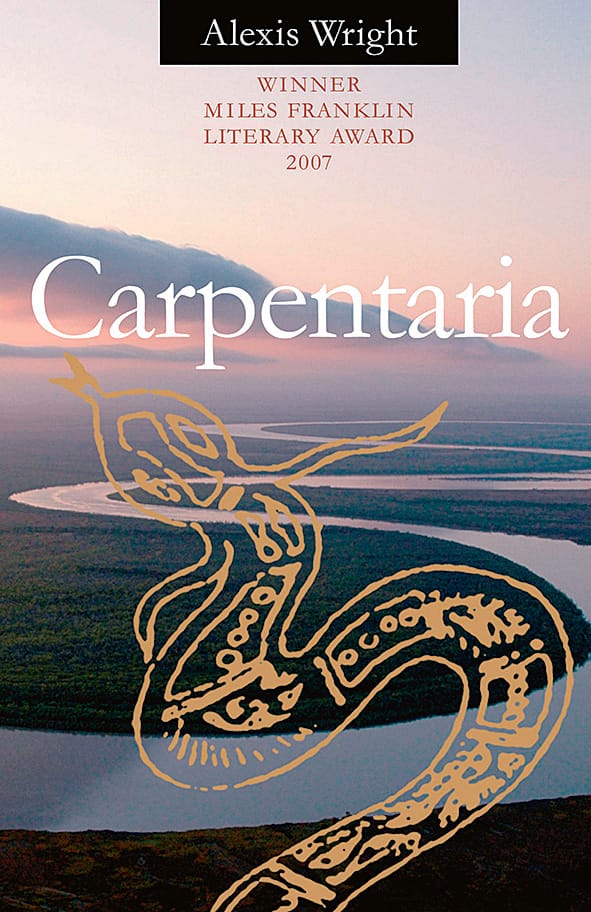

Carpentaria, Alexis Wright’s second novel, was published in 2006 by Giramondo, after every major Australian publisher had rejected it. It quickly collected a batch of literary awards, including the Miles Franklin, along with copious critical praise. It’s been translated into multiple languages and is studied at universities worldwide, from France to China.

At home and abroad, Wright, a Waanyi woman from the Gulf of Carpentaria, is regarded as one of our very best writers, and Carpentaria the best place to begin to read her. I felt duty-bound to tackle it.

One of my methods for getting through a big book these days is to move between the page and the headphones, reading when I have a chance and listening at other times. It meant I could take in Wright’s complex story as I walked to work, or while I hung the washing.

Listening is a little slower than reading, and it gave me more time to really imagine what I was hearing. Like the face of Angel Day – a woman who “had always been a hornet’s nest waiting to be disturbed” – or the house she shared with her husband, Normal “Norm” Phantom, with its echoing tin-floored corridor curved like a seashell or inner ear. Reading, on the other hand, shifted my attention to Wright’s skilful prose – by turns lyrical and bracing, marked by striking images and deep insights. Moving between audio and print also meant I could always be in the story for at least part of my day, no matter how busy, which is important in a book with many characters and a complex narrative structure.

As duty quickly gave way to pleasure, the audiobook became my preferred mode. I was often spellbound as I listened, my own imagination so stimulated that it sometimes flew off in the wrong direction, and I had to bring myself back to the story. The experience reminded me of listening to Ulysses – another Covid project – which I allowed to wash over me without worrying too much if I was distracted or lost track for a moment.

Like Ulysses, Carpentaria is epic in scope, and propelled by an ambition to reshape a national literature. Rich with allegory and literary reference – the Bible, James Joyce himself, Gabriel García Márquez – the book is alive with countless echoes, only partially detectable by a white reader like me, to the many stories of ancestors and Country that crisscross the text.

Wright brilliantly renders the authentic vernaculars spoken in her imaginary white town of Desperance, where everyone’s name is Smith, and in the Pricklebush, where Aboriginal families shelter among that invasive species on Desperance’s fringe. These voices are brought to life by Isaac Drandic, a Noongar playwright and director, who nails the book’s humour and irony.

But it took me a while to work out what Wright was doing, and at first I felt lost. Why were her scenes going on for 10 pages when they could be told in one? Am I in the present or the past? Is this stuff really happening or is Norm Phantom dreaming?

With some patience and some determination to find my way into this book, I eventually understood that Carpentaria echoes oral storytelling traditions, where the storyteller is in no hurry, goes off on tangents, moves back and forth in time and requires many sittings to get her big story told.

Wright says she wanted her book to be “written like a long song, following ancient tradition, reaching back as much as it reached forward, to tell a contemporary story”. She does not deal with linear time as my culture and my own literary tradition render it, but with deep time – the “everywhen” of Aboriginal reality, myth and spiritual experience. I soon realised this was a book I would want to read again, and that it would reward a second and third reading.

The serpentine style of the story means the mysteries at Carpentaria’s heart deepen slowly, and new intrigues are layered on older ones, with everything building to a tense crescendo at the local mine. This last part of the book was so gripping I had to ditch the headphones and instead turn the pages at top speed, dying to find out what would happen to Norm, his son Will, friend Mozzie Fishman and grandson Bala.

Wright throws everything at her story: her startling originality, her deep learnedness and her love for her people, as well as fire, flood and a vicious cyclone that will turn the world of Desperance upside-down, just as she turns the reader’s expectations upside-down over and over again.