On a farm on South Australia’s Limestone Coast, Rebecca Starling applies global gardening knowledge to micro business principles.

Words Christine McCabe

Photography Christopher Morrison

SIX years ago, Rebecca Starling crossed the world to plant flowers on an isolated stretch of South Australia’s Limestone Coast. It was a long way from Britain, a challenging place to garden, and a very different way to live. She left a corporate job in England and with her husband James relocated to his family’s fifth-generation cattle and sheep farm, near the coast between Kingston and Robe.

Cuffed by the Coorong’s haunting estuarine lagoons made famous by the book and movie Storm Boy, the low-lying Limestone Coast has some of the state’s best farmland, and a landscape riddled with mystery: dormant volcanoes, wild seas and seemingly bottomless sinkholes that attract free divers from around the world. Starling was struck by the flat landscape, the dry “biscuit-coloured” paddocks and enormous river red gums. “My strongest first impression was the overwhelming smell of eucalyptus,” she says. “Every time I stood on some dried leaves the heady fragrance was released.”

Her first move was to requisition the farm’s old bull paddock, before establishing a handful of garden beds, ordering seeds and bulbs, laying weed mat and setting up irrigation for the summer. She quickly realised the region’s sand over limestone soils and maritime climate were well suited to growing flowers, despite the coast’s punishing winds.

Today Starling’s 1.2 hectare flower farm is a wonderfully life-affirming place,

thrumming with bee buzz and bird song, bordered on one side by an old orchard and a collection of 19th century stone farm cottages and on the other by towering eucalypts.

Starling carries a bunch of Watsonia ‘Lilac Towers’; roses in abundance; an abandoned farm vehicle flower-bombed during a season of excess; roses in abundance. Photography by Christopher Morrison.

With a windbreak of native Australian shrubs including tough, tall kangaroo paws, the farm is divided into large beds spilling with old-fashioned flowers. Depending on the time of the year, the beds bear heirloom chrysanthemums in soft sepia tones, twining sweetpeas, lush Italian ranunculus in saffron and carmine, and roses the colour of milky coffee, with delphiniums and foxgloves looming like divas above the crowd.

These colours and tones are worth noting, because as a flower farmer and florist, decorating dozens of weddings every year, Starling is required to remain one step ahead of flower fashion.

Take dahlias. Once considered brash and thoroughly démodé, today they have a strong hold on the horticultural imagination. They are Starling’s most demanding crop and a particular passion. Yet even when digging thousands of dahlia tubers in the mucky and murky depths of winter, she somehow manages to retain her poise. I’m reminded of legendary English gardener Vita Sackville-West: tall, impeccably mannered and smartly turned out. If somewhat muddy.

Starling would likely hate this description. But she does love this new, muddy version of herself as she sets out early every morning, always with Ivy the flat-coated retriever by her side, to harvest flowers before the heat of the day.

When she married James in London more than a decade ago he was working in finance, but she knew from the outset they would one day return to the family farm. Always at the back of her mind was the question of what she might do there. A case of farmer’s wife needs a new career. A love of gardening was somewhere to start, because no matter where her work life took her, even the Swiss Alps, Starling made gardens, relishing winter nights by the fire scouring plant catalogues and weekends in the greenhouse, experimenting with growing flowers and vegetables from seed.

“I was amazed at how much better the tomatoes tasted,” she says, “and the incredible range of flowering plants, things I’d never seen in a garden centre.”

Keen to learn more, she signed up for courses with the Royal Horticultural Society in London. When James relocated to the US, she enrolled in a master gardener program and studied at the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx, where her knowledge grew exponentially. “I learned to garden under very different conditions, much colder winters but hotter and significantly more humid summers,” she says. “Plant fashion was also different. In England, cloudy skies provided a milky soft light, favouring pastel tones and loose silhouettes. But in New York, dinnerplate-sized hibiscus flowers sizzled under the bright, hot sun and vibrant primary colours were celebrated.”

One autumn weekend, James and Rebecca took a road trip to Vermont, where a small farm stall selling vegetables and locally grown cut flowers caught her eye.

This humble stall was to prove the solution to her Australian work dilemma. Stacked with bunches of dahlias, it was a small cog in a much larger micro flower-farm movement creeping across the US and Europe (and latterly Australia). Rather than producing large quantities of a limited number of varieties in hot houses like the large commercial growers, micro flower farmers grow a wide selection of seasonal flowers in fields, without pesticides and herbicides. It’s the flower equivalent of the slow food movement, from seed to vase rather than paddock to plate.

Candy pink roses make a classic cottage-garden arrangement; Starling’s micro flower farm. She says a space the size of a large dining table can produce cut flowers for much of the year. Photography by Christopher Morrison.

When Starling arrived on the Limestone Coast, she found herself tackling radically different growing conditions to the northern hemisphere. It was a case of trial and error. Crops failed. Weeds took over – the grass-seed load from the old paddock seemed never-ending. Snakes and kangaroos became her gardening companions. She threw out many of those “how to” books from Britain, and through hard work and late-night research mastered an entirely new gardening regimen, relishing the much longer growing season. No snow, no hard frosts. She discovered Australian and South African native flowers and loved the chance to celebrate the bold colours she had come to appreciate in New York and that stood up so well to a bright Australian sun.

As her small flower farm established, Starling began supplying cut flowers and bouquets to local businesses and weddings.

I met Starling just as her farm was starting to thrive. I grew up on the Limestone Coast and still love spending weekends in Robe, especially in winter, taking wild beach walks with the Southern Ocean roaring like a thousand jet engines. And it was on one of those cold winter days during Covid that I bumped into Starling.

We made an instant connection as gardeners often do and were soon running cut-flower workshops in my little garden studio in the Adelaide Hills. These classes were joyous affairs. Starling arrived with buckets of flowers, and we made bouquets or Dutch Masters-style centrepieces while she explained how to design and maintain a cutting garden. With careful planning, a space the size of a large dining table is all that’s required to have cut flowers for much of the year.

Class participants were highly engaged; many were women looking to make a

pivot in their career, and we soon realised there wasn’t a book available on the subject of growing cut flowers in Australia, whether for the home or as a micro flower farmer. So we wrote that book, distilling a lifetime gardening on both sides of the globe.

In winter, Australia imports up to 90 per cent of its flowers; 50 per cent at other times. “This book aims to encourage more people to grow, buy and sell as locally as possible,” says Starling. “Many flowers like dahlias do not travel well so need to be sourced locally. I would love to see a little flower farm on the outskirts of every town.”

And what’s next on the flower fashion front? Starling is making a case for carnations. Stay tuned.

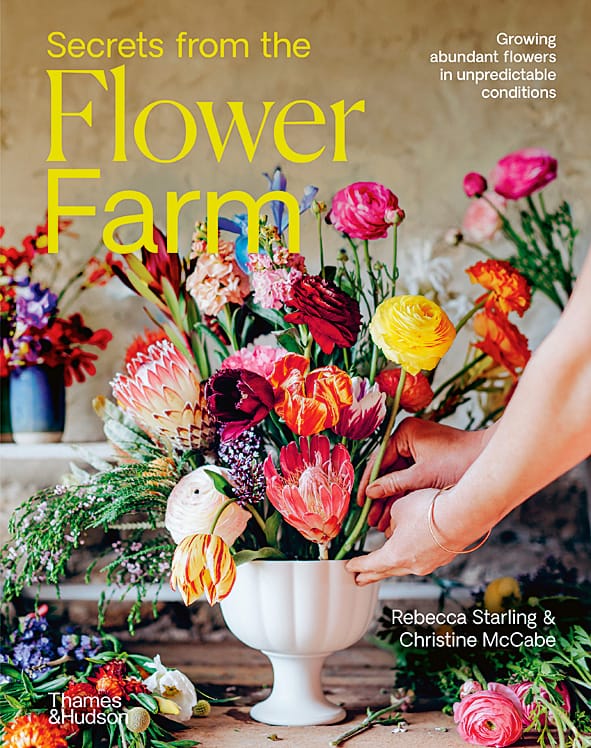

Read more in Secrets from the Flower Farm, by Rebecca Starling and Christine McCabe (Thames & Hudson Australia, $59.99).