Fourteen years ago East Orange had a problem. Fortunately, Paula Townsend had a solution.

Words Ryan Butta

Photography Pip Farquharson

GALAH is highlighting the lives of ordinary people in our rural and regional communities, in a series made possible by our partnership with Westfund, a not-for-profit health fund with a 140-year history in rural Australia.

A few years ago, when Paula Townsend was looking for a place to buy in Orange, she called up a real estate agent. ‘Well, you don’t want to buy in East Orange,’ she was told. Paula didn’t mention that she was born and bred in East Orange. It’s a prejudice she had become used to, even though she couldn’t understand it. ‘Orange is very West Orange/East Orange. Although everybody ends up in East Orange because the cemetery is here.’

Things are changing, however, and Paula proudly tells me that East Orange is now often referred to as ‘trendy East Orange’ with a ‘village atmosphere’. If the image of East Orange is indeed changing, it is in part because of the work Paula herself has been engaged in for the past 14 years at the Bowen Community Technology Centre.

‘In the summer of 2005 and 2006, there were a lot of disturbances. There were three houses burned in one street in a week. There were older people who were too scared to even get their mail. Houses were egged, or rocked or whatever, and there were people too scared to walk around.’

Deciding that the police wouldn’t or couldn’t help, Paula organised a community meeting. The meeting had to be relocated to a nearby park after 200 people turned up to discuss a problem that was fast getting out of hand.

The centre is part of a community that has been overlooked and underfunded in the past. Photography by Pip Farquharson.

The problems would not be solved with more policing. Paula explains: ‘It is an area of low socioeconomic levels. There are a lot of people here who have family members in prison at the moment or juvenile detention. We’re looking at families suffering from intergenerational unemployment. Neglect. Numeracy and literacy are a big problem with the adults.’

The solution that came out of that public meeting 14 years ago was the Bowen Community Technology Centre. The centre has become a safe place where children and adults can drop in whenever they want (but if children turn up during school hours they can expect to be met with a hard line of questioning).

While people drop by to use computers and printers, Paula believes that what the centre really offers is a place that cares about the community. ‘I always say hello to whoever comes in, I don’t care who they are. I’m sort of looked on as the tough grandmother. We have very few rules, but if you don’t stick to them, don’t let the door hit you on the way out.’

If Paula sounds tough it’s because she’s needed to be. When the centre first opened, Paula and other locals from the community would stand guard outside, protecting it from those who wanted to tag it with graffiti and others who wanted to knock it down. Then in 2008, on crutches as she recovered from a hip operation, Paula herself was attacked by a child of no more than 11 years old. ‘He knocked me down. I got myself back up and said to him, “have another go”. I had to stand my ground. They had to learn that I wasn’t scared. But I was scared. Truly scared.’

After the centre was up and running Paula turned her attention to another problem. ‘There used to be only one way in and one way out of this area,’ she tells me. People felt closed off, locked in and forgotten. Paula set about campaigning for a pedestrian bridge that would open up access to the neighbourhood, confronting local politicians who had long promised better access. Paula points out the bridge to me, proud of her role in getting it built. The bridge represents more than

access, it represents the recognition of the needs of the community. ‘It was a forgotten area,’ Paula says. ‘And nobody deserves to be forgotten.’

Today the Bowen Community Technology Centre houses 14 computers that are free to use. Printing is also free. If you need a résumé typed up or a job application filled in, Paula will do that for free too. ‘I’m not a very good typist, but I get it right.’ Paula has lost track of the number of jobs she has helped people get or how many thousand children have passed through the centre.

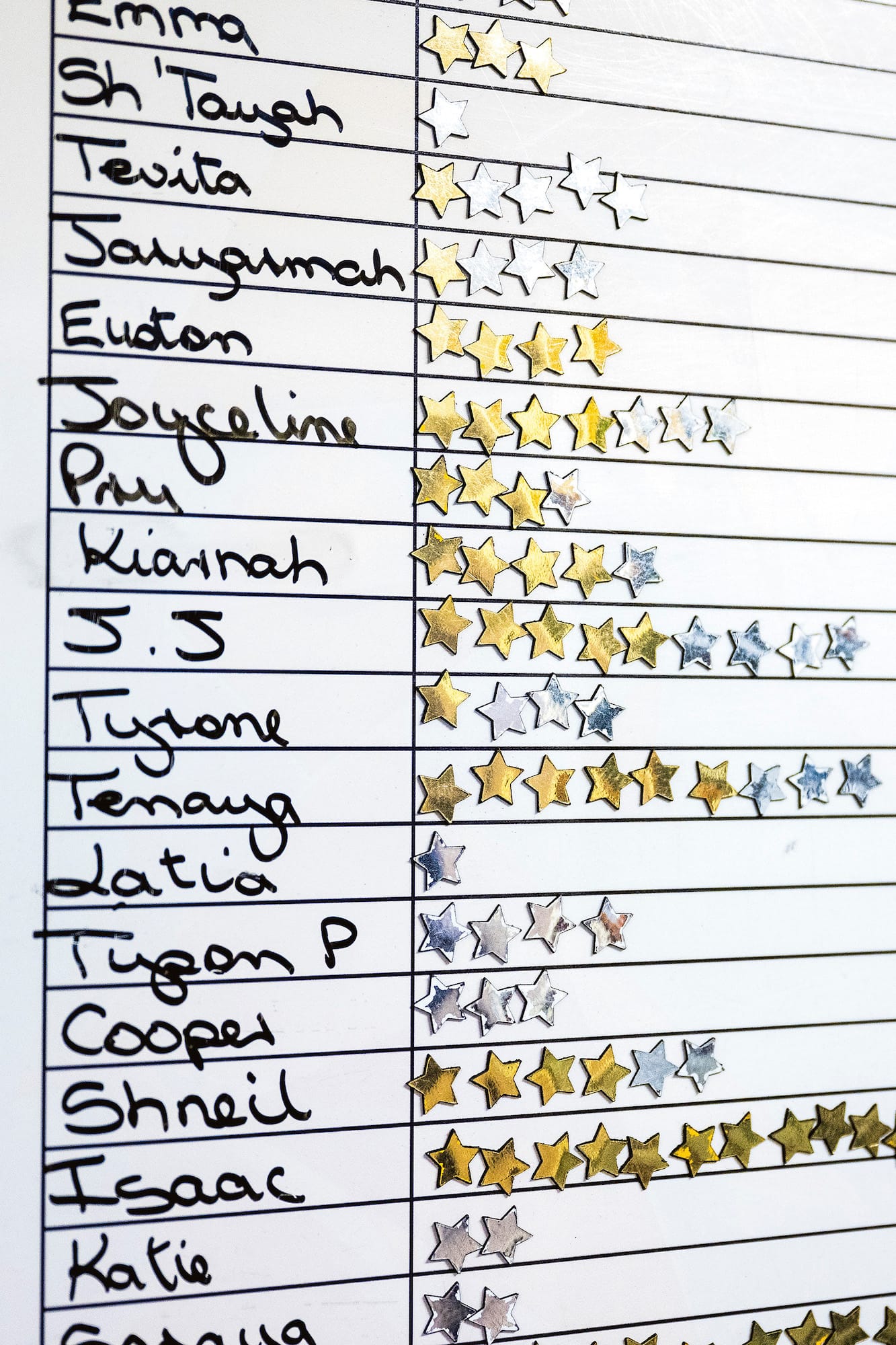

‘Not long ago, I heard from a girl called Mary. She looked me up on Facebook and said, “You might not remember me”.’ But Paula did remember Mary. Paula would give the children word puzzles and each completed puzzle would be rewarded with a chocolate. Mary told Paula that, though she only did the puzzles for the chocolates, the puzzles had given her a love of words and led her to start studying law.

As Paula and I talk, Terry, a man in his thirties, walks in and takes his place at a computer. Terry is scrolling through house listings and I interrupt to ask him what he likes about the centre.

‘It’s sort of relaxing. You can take your time here. Paula is good for a chat and it’s not too noisy. Paula is a big encouragement for me. I lost my mum recently, so yeah, it’s good to chat.’

I let Terry get back to househunting. I ask Paula what she has learned over the past 14 years. She doesn’t hesitate in answering. ‘I’ve learned that everybody is an individual and they need to be treated individually. Everybody likes a little bit of care. Everybody needs rules. Everybody needs a bit of fun. And I get the most fun every day because I have the best job in the world.’

To find out more about Westfund, including the Westfund Community Grants Program, visit westfund.com.au