Celebrating the life of the virtuosic artist Emily Kam Kngwarray.

Words Mark McGinness

EMILY Kam Kngwarray emerged as if from nowhere in the last quarter of last century. Instantly recognisable, her lush, joyous canvases sing with a glorious sense of rhythm and light. But she wasn’t from nowhere; she was from Utopia, an area of 2000 square kilometres belonging to the Anmatyerr and Alyawarre people, 250 kilometres north-east of Mparntwe/Alice Springs.

Kngwarray’s home was Alhalker, a rock-hole in south-western Utopia. Here the emu, the finger yam, the green bean, the bush yam, the bush potato, and the bush plum were sung in ceremony. The atnulare yam from Alhalker was Kngwarray’s main story, and a yam was always coursing through her canvases. She owed her middle name to its seeds, or kam. She was always part of the country she painted.

Kngwarray rarely spoke of her work, and then it was in her own language, Anmatyerr. In 1990 she described her imagery to Rodney Gooch, a long-time manager of the Central Australian Aboriginal Media Association, which facilitated the sale of her work: “Whole lot, that’s whole lot, Awelye (my Dreaming), Arlatyeye (pencil yam), Arkerrthe (mountain devil lizard), Ntange (grass seed), Tingu (Dreamtime pup), Ankerre (emu), Intekwe (favourite food of emus, a small plant), Atnwerle (green bean), and Kame (yam seed). That’s what I paint, whole lot.”

Born around 1910, Kngwarray was brought up on the traditional wisdom of her people and would become the keeper of several song cycles. She didn’t see a white man before she was nine or 10 — a policeman on horseback leading an Aboriginal prisoner in chains. A commanding, independent young woman of great strength, she eschewed domestic employment unlike most of her sisterhood and, after moving in 1934 to MacDonald Downs in south Utopia, she took a job as a stockhand riding camels as cattle properties were established on their lands.

Donald Holt, the owner of Delmore Downs station and a grandson of the Chalmers who had settled on adjacent MacDonald Downs in 1921, recalled selling necklaces and bead maps in 1972-73 made by Kngwarray from eucalyptus, acacias and bean trees.

She married twice and had no children of her own. Her greatest friend, the eldest daughter of Alyawarre elder Jacob Jones, Lily Sandover Kngwarray (born on MacDonald Downs), bore a son to Emily’s ex-husband, and Lily’s children and grandchildren became Emily’s, too.

In 1977, the Utopia Women’s Batik Group was founded. In fact, Kngwarray had been drawing in the sand and painting for decades, including the traditional body-marking of the Anmatyerr women’s ceremony, awelye. During awelye, Anmatyerr women painted Dreaming designs on their chests and shoulders fusing earth and body with pigments ground from the earth, chanting their Dreaming as they painted.

Kngwarray took to applying these ceremonial motifs to silk and did so with assurance and dexterity, although she disliked the fumes of the batik wax. In the summer of 1988–89, the Alhalker women were introduced to acrylic on canvas by Gooch. Kngwarray’s first acrylic painting, Emu Woman, was really a continuation of her emu feather on batik, a composition of signs connecting Kngwarray with the Emu Dreaming. In a sense, she had been preparing for this for most of her life. Composed only of dots and lines, it was a remarkable departure from the Papunya style of desert painting because it represented “women’s business”: food gathering, bush tucker, the seasonal moods and habits of local flora, fauna, and other aspects of day-to-day camp life at Utopia. She would switch effortlessly between styles but Kngwarray had found her metier.

By 1990, Kngwarray was spending time at Delmore. She and Don Holt’s wife, Janet, became friends and much of her best work was produced here. Janet recalled one day at Delmore in 1990 when Kngwarray returned with a canvas, given to her by Don a month earlier, tied to the roof of a Holden HQ. A young girl helped Kngwarray carry it across a riverbed with one end dragging in shallow water, the rest covered in dust. After washing, drying and hanging it under lights, the Holts realised it was a masterpiece. Within a week, Untitled (1990) was selected by director James Mollison for the National Gallery of Victoria.

Janet later showed Kngwarray a Matisse colour chart from which to paint. Kngwarray paused and responded, “Whole lot.” The result? A burst of colour. One of her Sydney gallerists, Dominic Maunsell, proclaimed her “our greatest colourist” — likely to eclipse Sidney Nolan.

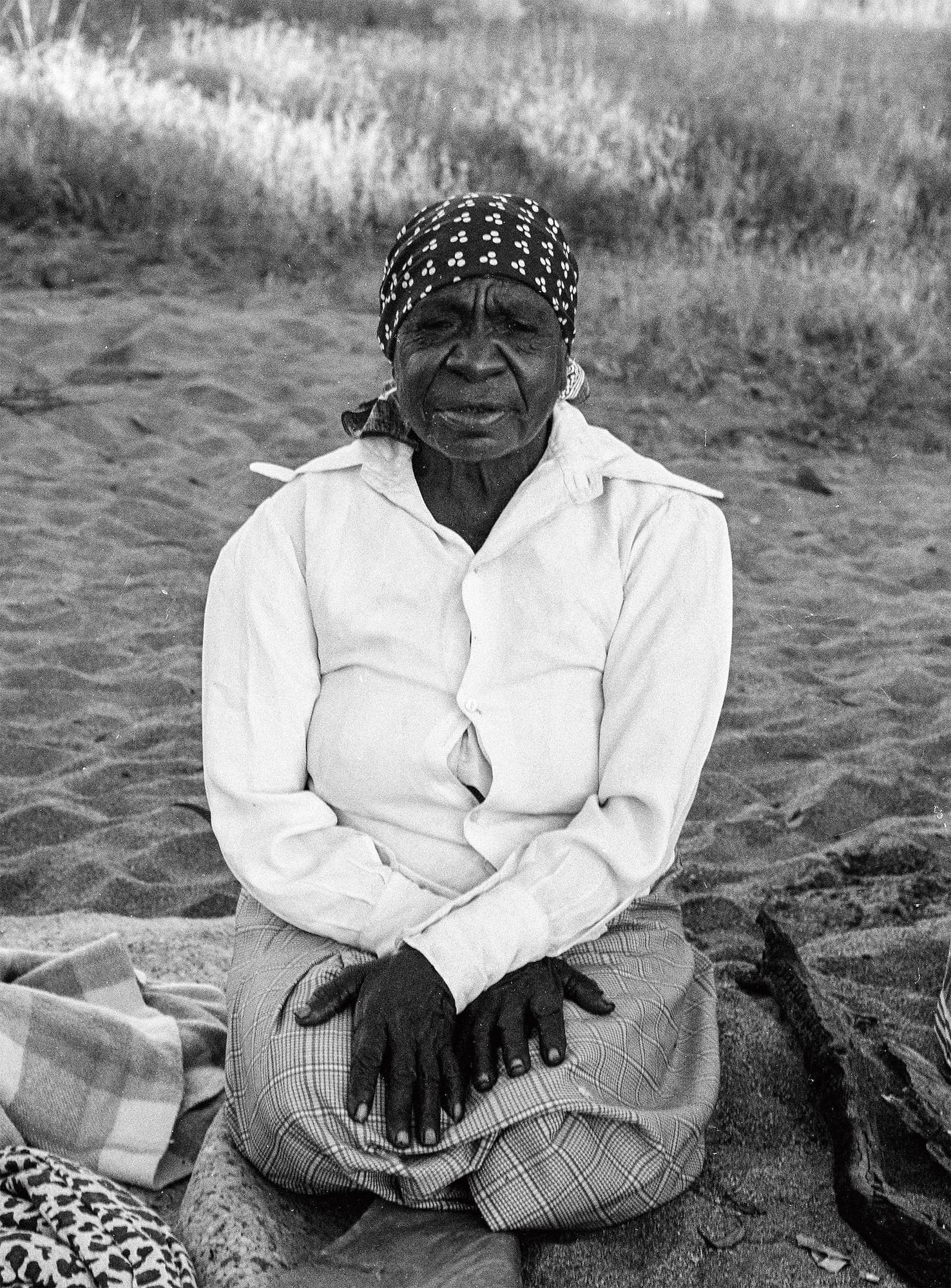

Maunsell, who got to know her quite well, described, “The face! The face is fabulous. I mean she looks like a genius.” Kngwarray had a marvellous smile and a mischievous laugh, her nose pierced as a homage to her ancestor Alhalker, a pierced rock standing on her Country. Journalist Jane Cadzow in a profile for Good Weekend magazine wrote that “wisps of silver hair escape from under a woollen hat, knitted in the colours of the Aboriginal flag. Her hands are gnarled; her face weathered from eight decades spent outdoors.”

Her early work was linear overlaid by careful dotting. During 1990, as London gallerist Rebecca Hossack put it, “this underlying tracery began to disappear beneath a profusion of dots”. There were gestural swipes and clotted dotting. The Age journalist Sonia Harford wrote evocatively, “Emily’s dots are like wattle when it brushes against your face. Shot through with the colours of the desert, her art shimmers with the heat of the land.” Kngwarray sustained this act of dotting throughout most of her career, embracing its value in traditional Aboriginal visual culture.

She always sat cross-legged on the ground as she painted, rarely moving from that one position. The painting was turned to suit her reach, or with large works she sat on top of different areas of the canvas giving a constantly changing perspective and a coherence as she moved around the canvas.

From mid-1990 she showed her preference for her main colours: red and yellow mixed with white, which happened to be the Alhalker ceremonial colours. But come the rain, she would produce the mesmerising image that graces the cover of this issue of Galah — a profusion of the yam in flower, like glorious strings of white and pink pearls.

The receipt of an Australian Artist’s Creative Fellowship in 1992, a solo show three years later at Parliament House in Canberra, and the enthusiasm of curators such as Margo Neale and Akira Tatehata brought Kngwarray fame, fortune, and inevitably pressure from collectors and her community. Until 1994, the Holts estimated that they and Gooch had bought 98 per cent of Kngwarray’s output. She had little interest in her new wealth. Don Holt estimated that Kngwarray bought some 500 cars for her community and gave away most of her cash. She lived frugally, sleeping in a bough under the stars — “her 5000-star hotel”. At Delmore, she camped under a big bloodwood gum.

When asked to speak about her art, Kngwarray would refer instead to her people, her identity, and her land. Filmed in 1996 holding one of her canvases, she pointed to the painting and then to particular areas of surrounding Country. As Dr Sally Butler suggested in her 2002 thesis, “Her gestures ... are largely a re-enactment of what was required in giving evidence for the Utopia Land Claim.” She concluded, “Perhaps [Kngwarray] wanted to ensure the whitefella never loses sight of the evidence given in the Utopia land claim, and never forgets the legitimacy of Anmatyerr/Alywarre land ownership. Her artwork is arguably more comprehensible as a sustained demand for legal and moral recognition, than it is as an expression of cultural authenticity for uninitiated audiences to whom the iconography is largely incomprehensible.”

In 1979 Kngwarray had participated in giving evidence of awelye as part of the Utopia land claim. Utopia had been established as a pastoral lease in 1923 and sold to the Central Land Council five years later. The council then re-leased the land to the Anmatyerr, Alyawarre and Kaytetye owners. In 1979, these communities instigated formal proceedings to gain freehold title of Utopia, and parts of these proceedings took place in Utopia. Required to “prove” how customary body markings, sand stories, and ceremonies connected Anmatyerr and Alyawarre people to that land, Kngwarray and other elders performed body painting, singing and ceremonies. And they succeeded.

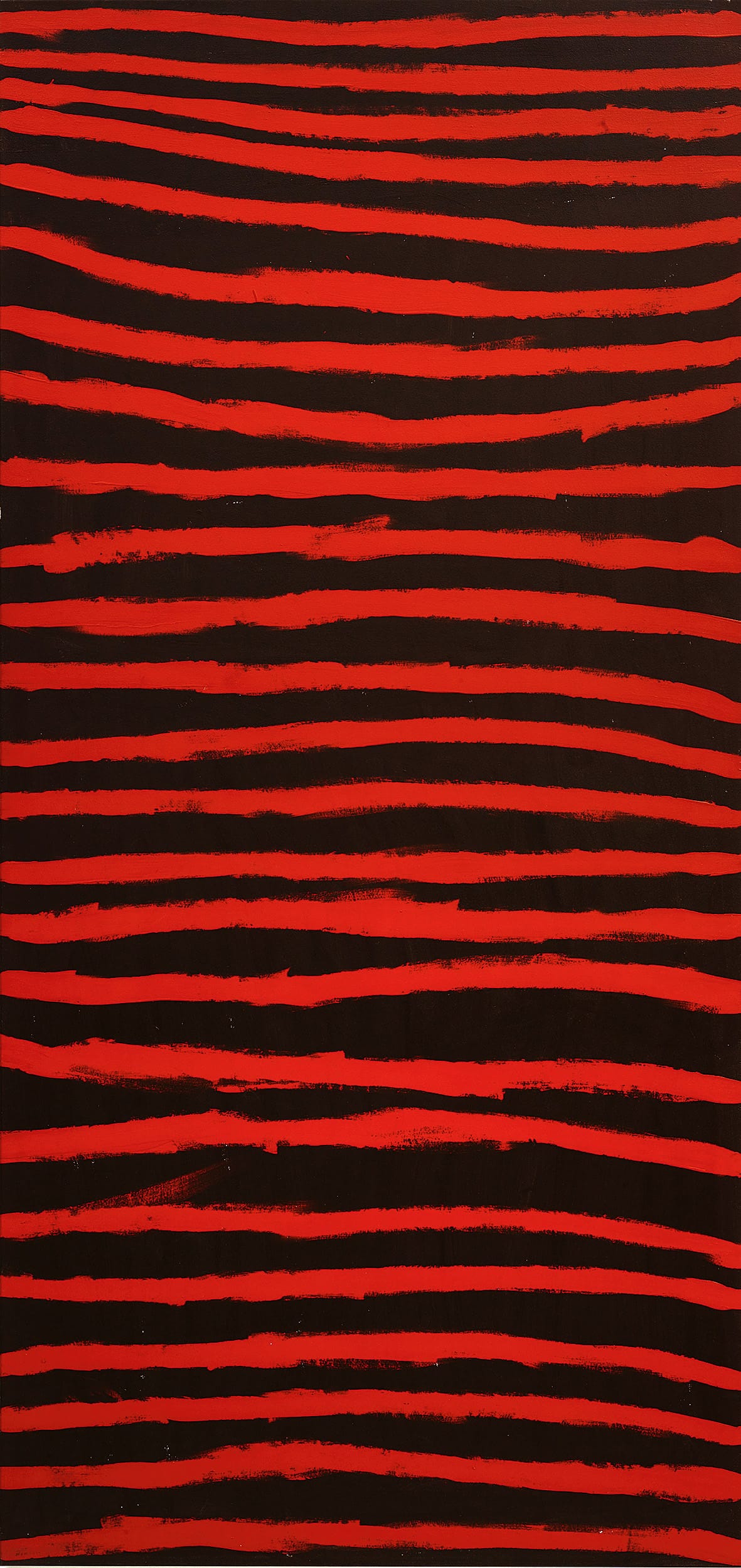

The abiding significance of awelye continued on canvas as it had on her skin - seen above in Untitled (Awelye), 1994: ochre stripes on black so powerfully sombre. From 1993, she had taken to lines, a new minimalist dimension. In that vein, see her stripes with perpendicular connecting lines, beautifully executed above in Untitled (Awely), 1994.

Kngwarray’s last two months were spent at Delmore, her dedication and energy prodigious. In 1995, the last full year of her life, she had painted the huge Anwerlarr anganenty (Big Yam Dreaming), her most monumental canvas since Earth’s Creation the year before. In the final two weeks of her life, and short of materials, Kngwarray embarked on Final Series, My Country (1996), a collection of her last work. A Sydney gallerist marvelled, “With no other materials, she dipped her one-inch gesso brush into a pot of paint. Over the next few days Kngwarray painted 24 canvases like nothing she had ever done before.”

She died, at the age of about 86, in Alice Springs on 2 September 1996, leaving more than 3000 paintings of varying quality but many of them mesmeric masterpieces, all created in a mere eight years. Kngwarray’s example and success encouraged another generation of female Aboriginal artists.

Emily Kam Kngwarray’s genius not only inspired and enriched her people but irrevocably transformed the reach and reputation of Australia and Australian art.

Tate Modern in London, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Australia, is showing the first major solo exhibition in Europe of Emily Kam Kngwarray’s work, until 11 January 2026.