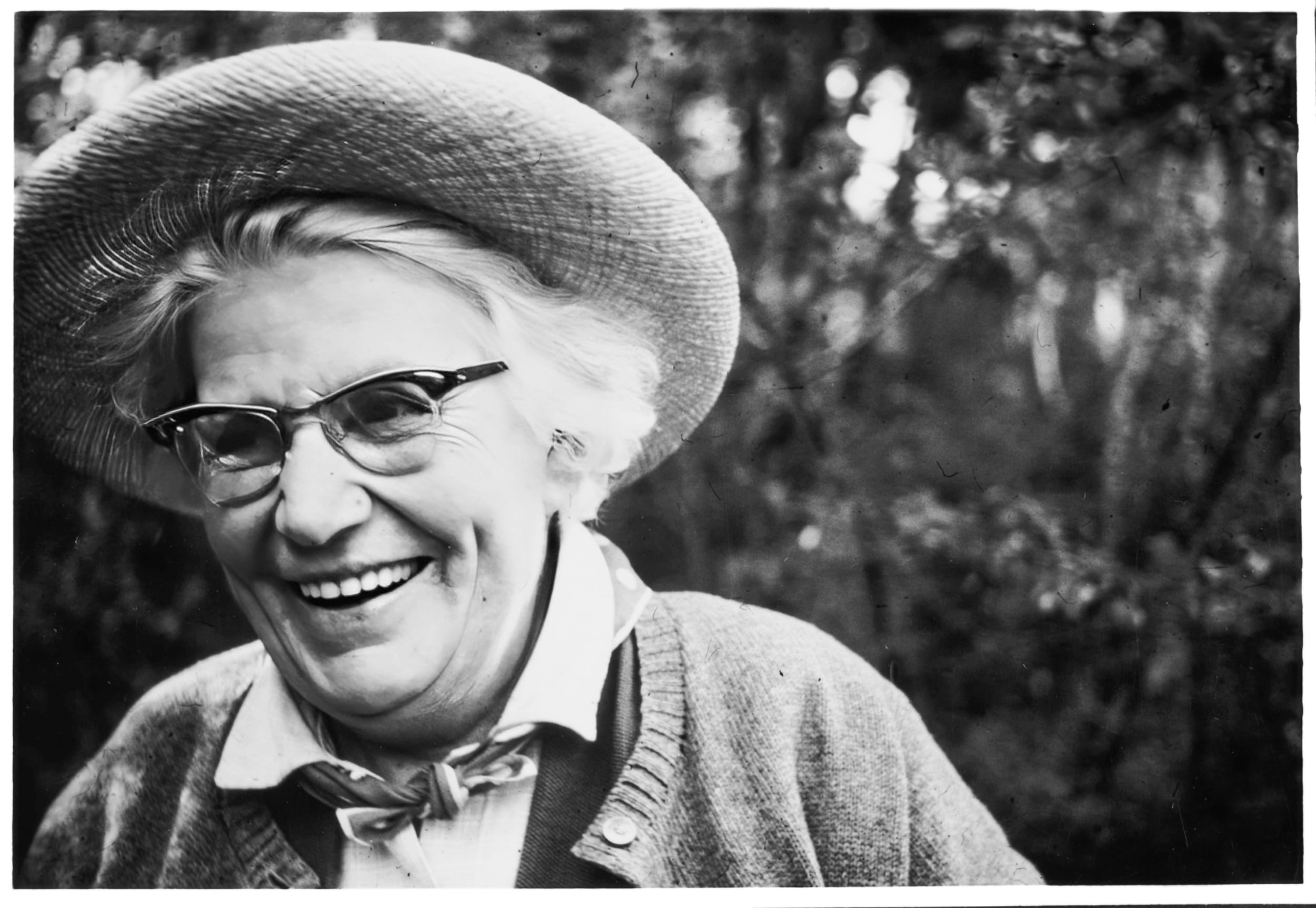

Galah's obituarist Mark McGinness remembers Australian landscape designer Edna Walling.

EDNA Walling memorably wrote, “Though there is no brilliant foliage coloration in Autumn, no exciting burst of Spring, no exquisite tracery of the branches in Winter, and none of the ‘green thought in a green shade’ in Summer, about the Australian landscape, the thought of any journey to a place where the trees and natural ground cover are still unspoilt is thrilling to me.”

This vivid delight in the natural beauty of her adopted country underscores why Edna Margaret Walling was not just Australia’s most celebrated female garden designer but one of its greatest. Over six decades, she designed some 350 gardens from Hobart and South Australia to Queensland. These commissions were chiefly for the wealthy but, through her magazine columns and her books, she became a household name, influencing even those who could not afford to commission her.

She was born on 4 December 1895 in York, England, the second daughter of William Walling, then a furniture dealer’s clerk, and his wife Harriet Margaret, née Goff. The family soon returned home to Plymouth in Devon, then to the village of Bickleigh. This was where young Edna often walked about Dartmoor with her father who, as a Christian Scientist, was devoted to nature. He treated her as the son he didn’t have. From these walks she developed an “intense love of low-growing plants, of mauves and soft greens, of mossy boulders and gritty pathways and closely nibbled turf”. Her formal education was at Plymouth’s best school and then, after a business reversal, at the convent of Notre Dame.

After his shop burnt down, William took his family to New Zealand in about 1911 in search of new opportunities. Edna worked briefly as a maid on a country property and began a nursing course.

Three years later the family moved to Melbourne, where William prospered as an importer’s agent. At her mother’s urging, Edna enrolled in horticulture at what is now Burnley College at the University of Melbourne and graduated knowing much about ploughing, pruning and fruit preserving. As her biographer Sara Hardy put it, Walling “became one of the new breed of ‘Girl Gardeners’, tending the trim lawns and straight borders of the well-to-do”.

On holiday in about 1919, Walling had a revelation when peering over a garden fence and lit upon a large curving stone wall: “That wall caught my imagination. I shall build from then on. Gardens for me became a chance to carry out the architectural designs going around in my head.”

She had taken to reading the work of English garden designer Gertrude Jekyll and architect Edwin Lutyens, whose work was in the Arts and Crafts style, as well as Spanish and Italian designers, and persuaded an architect friend to allow her to design a garden for one of his houses. “I aimed to unite house and garden,” she said.

More commissions followed, and by the early 1920s she had built a flourishing practice in garden design. Within a decade, she would be lauded in the press.

She wrote her first magazine story in 1921, and by 1926 she was contributing regularly to Australian Home Beautiful – and did so for two decades. Her columns brought her considerable popularity and influence. Hardy describes her style as “a provocative combination of artful knowledge and brutish charm”.

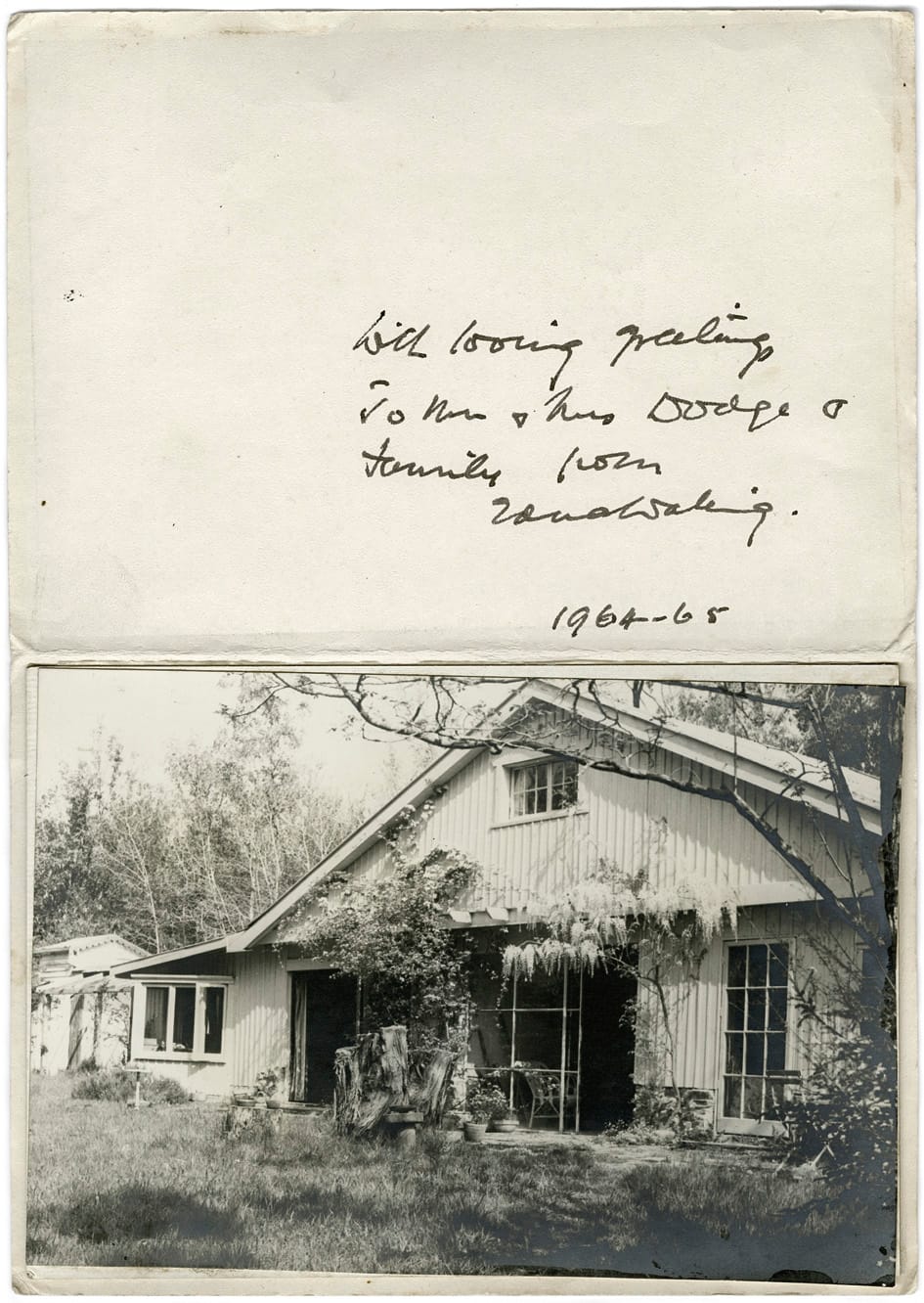

In 1921, a big year for her, she bought eight hectares at Mooroolbark, east of Melbourne, where she built her own house and called it Sonning, after the romantic village on the Thames she had first seen from the river at the age of seven. From here, she lived and worked and sold off blocks, gathering like-minded individuals – mainly women, for whom she insisted on designing their simple houses: English cottages of rock, timber and wooden shingles and country gardens of foxgloves, hollyhocks and Westmoreland thyme.

She named the community Bickleigh Vale village, another childhood tribute. On site, Walling always dressed in jodhpurs, jacket and tie, with no make-up and a man’s felt hat on a closely cropped head. Some called the village Trouser Lane; others Spinster’s Row.

Beyond the name-calling, Walling’s venture made her Australia’s first female property developer and Bickleigh, still in existence today, became a place of pilgrimage. Walling also designed several other estates, one of them for BHP at Mount Kembla.

In 1927, the great soprano Dame Nellie Melba called on Walling at Sonning. Melba had fired her male gardeners for accidentally mowing down her pansies with a newly invented mechanised mower. The dame wanted Walling to supervise the three “girl gardeners” hired to replace the men at her country house, Coombe Cottage, at Coldstream.

Hardy has recorded that Walling drew up two contrasting plans for Coombe: a relatively modest “garden of old-fashioned flowers” and a “water lily garden”. Dame Nellie was attracted to the latter but paled at the cost and what could have been a tribute to their friendship never took root. Even so, Walling always treasured a copy of Melba’s memoirs inscribed, “To Edna with love from Nellie Melba.”

In 1929, Walling was commissioned to design a garden at Langwarrin, south-east of Melbourne, for her Australian Home Beautiful publisher, Keith Murdoch. She designed the front garden, including the stone walls and the famed – now iconic – avenue of 129 lemon-scented gums that line the drive. During the next eight decades, Murdoch’s young bride, Elisabeth, increasingly made her own calls and Cruden Farm was indisputably her own.

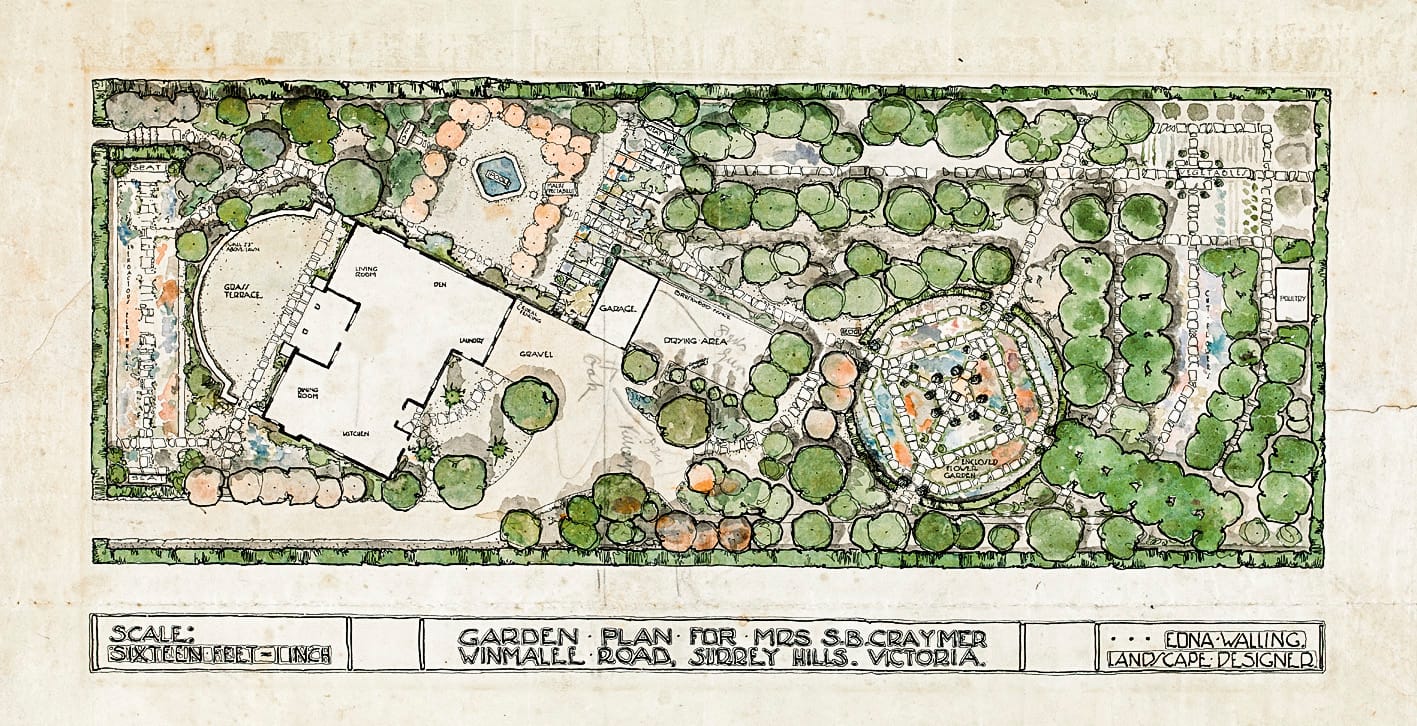

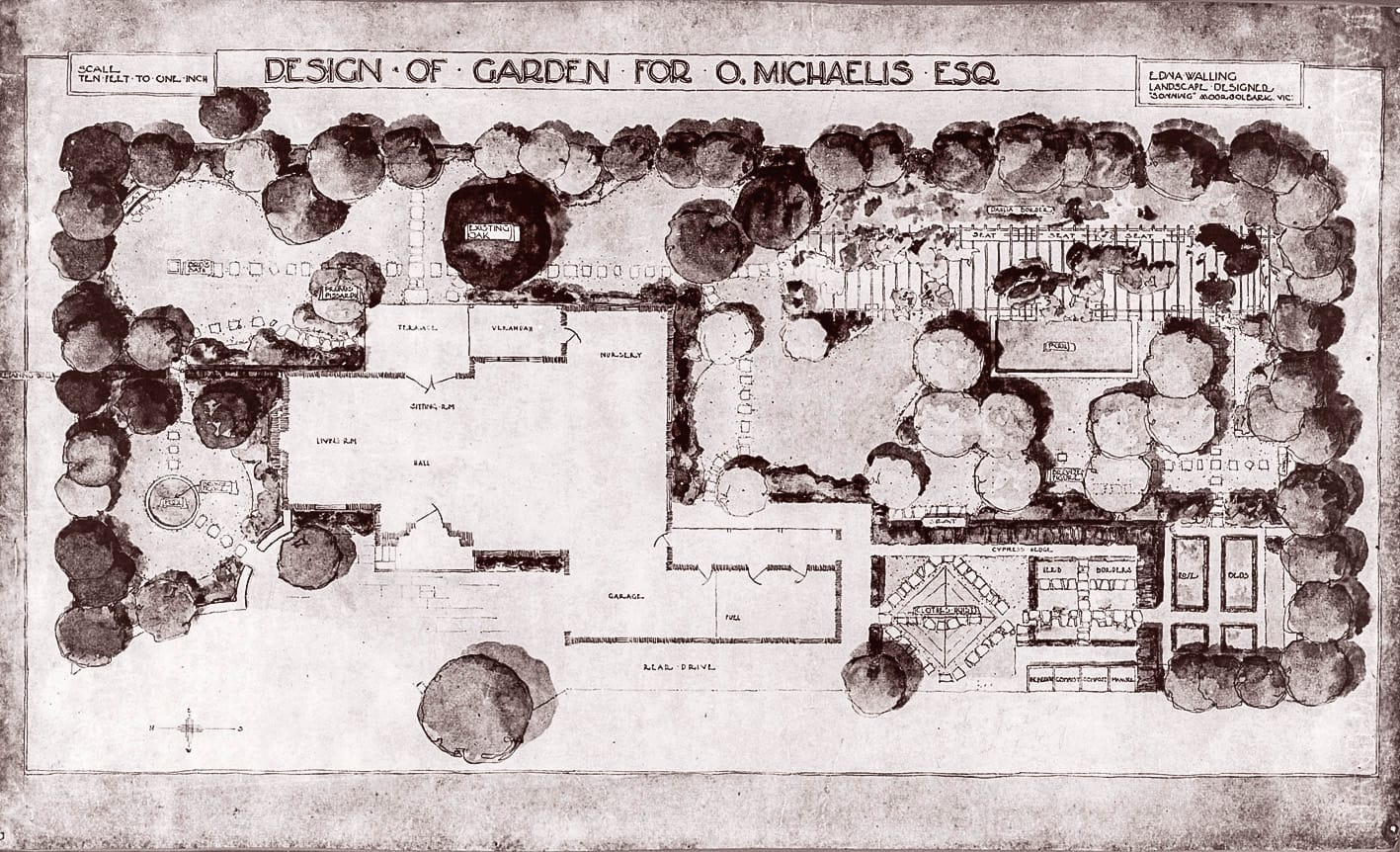

As Peter Watts, the author of The Gardens of Edna Walling (1981) put it, Walling’s vision extended beyond walls to “pergolas, stairs, parterres, pools and colonnades – woven into a formal geometry; but she always found a space for a ‘wild’ (unstructured) section.”

Many of her plans were exquisitely presented in watercolour and most of her gardens were constructed by her favourite stonemason, Eric Hammond. Other craftsmen who worked with her included Glen Wilson and Ellis Stones.

She designed gardens for wealthy clients in suburban Melbourne (many of which have since disappeared) and also in the Victorian countryside, including the hill stations of Mount Macedon and the Dandenong Ranges, and the Western District. Her design for The Grove at Mawarra Manor in the Dandenongs is among her most famous. As her fame spread, she accepted commissions in South Australia and New South Wales. The Ashton family’s Markdale and the Broadbents’ property Kiloren, both in the New South Wales Southern Tablelands, remain among the most perfect examples of her work.

Jennie Churchill, co-author with Trisha Dixon of Gardens in Time (1990) and owner of Kiloren for more than three decades, often heard the refrain: “You live in an Edna Walling garden? How wonderful!” She wrote how she loved Walling’s maxim that “a framework of hardy, proven performers is essential, and only then do you weave in the rare plants, the jewels. Deitzia, forsythia, viburnums, ribes, kolkwitzia, choysia, philadelphus, abelia, japonica – these are the reliable shrubs in our garden that just keep on keeping on, never failing to deliver pleasure for weeks on end.”

In a chapter devoted to Walling in Remembered Gardens: Eight Women and Their Visions of an Australian Landscape, garden writer Holly Kerr Forsyth saw Walling’s career in two phases. The first, a love for the English plants of her childhood; and the second, the influence of Lutyens and Jekyll and their homage to the structure and formality of the Italian Renaissance.

By 1951, 30 years into her career, Walling was captivated by Australia’s “light, its water masses and the arrangement of its indigenous flora, by its natural landscape”. She had planned her first native garden but found her patron, a Western District pastoralist, less than impressed. As Paul de Serville observed in an elegant review of Sara Hardy’s biography (The Unusual Life of Edna Walling, 2005) for Australian Book Review, “Her interest in native flora increased as it became more threatened.”

By the 1940s, she had become a household name. Four books were published: Gardens in Australia (1943); Cottage and Garden in Australia (1947); A Gardener’s Log (1948); and The Australian Roadside (1952). A monograph,

On the Trail of Australian Wildflowers, appeared posthumously in 1984.

But by the ’60s, Walling had difficulty being published and took to wallpapering a room with rejection letters. So she was surprised and overjoyed to see The Australian Roadside reissued in 1969. (Roadside would appear, revised, in 1985, and again in 2004.)

By the 1980s and 1990s she had become a cult figure in Australia, and her advocacy for naturalism and native plants was widely embraced.

Her message of low maintenance, too, was reassuring: “Once you have laid that path, planted that tree, and put in those rock plants, you can sit back and enjoy.” In the choice of her topics, she wielded her pen with a light touch. As de Serville put it, “The loyal middle-class readers who had her books on their shelves and whose tastes coincided with theirs ... stuck by her ideas despite the vagaries of fashion, because she provided an unfussy, informal recollection of ancestral memories and home.”

By 1967, she had moved to Buderim, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast hinterland, for the warmth and to be closer to her niece, the equally remarkable Barbara Barnes. Her old friend and editor, the poet Lorna Fielden, also joined her there, just up the road. In Buderim, as biographer Sylvia Martin noted, Walling became something of “a conservation warrior, writing to newspapers, councils and politicians not simply to complain about the destruction of the natural landscape but to suggest alternatives”. It was so Edna.

She died on 8 August 1973, at the age of 77. Walling was buried in Buderim cemetery just near what Hardy describes as a vibrant native tree “that bursts forth with intricate copper-coloured flowers in the summer – a Grevillea robusta”.