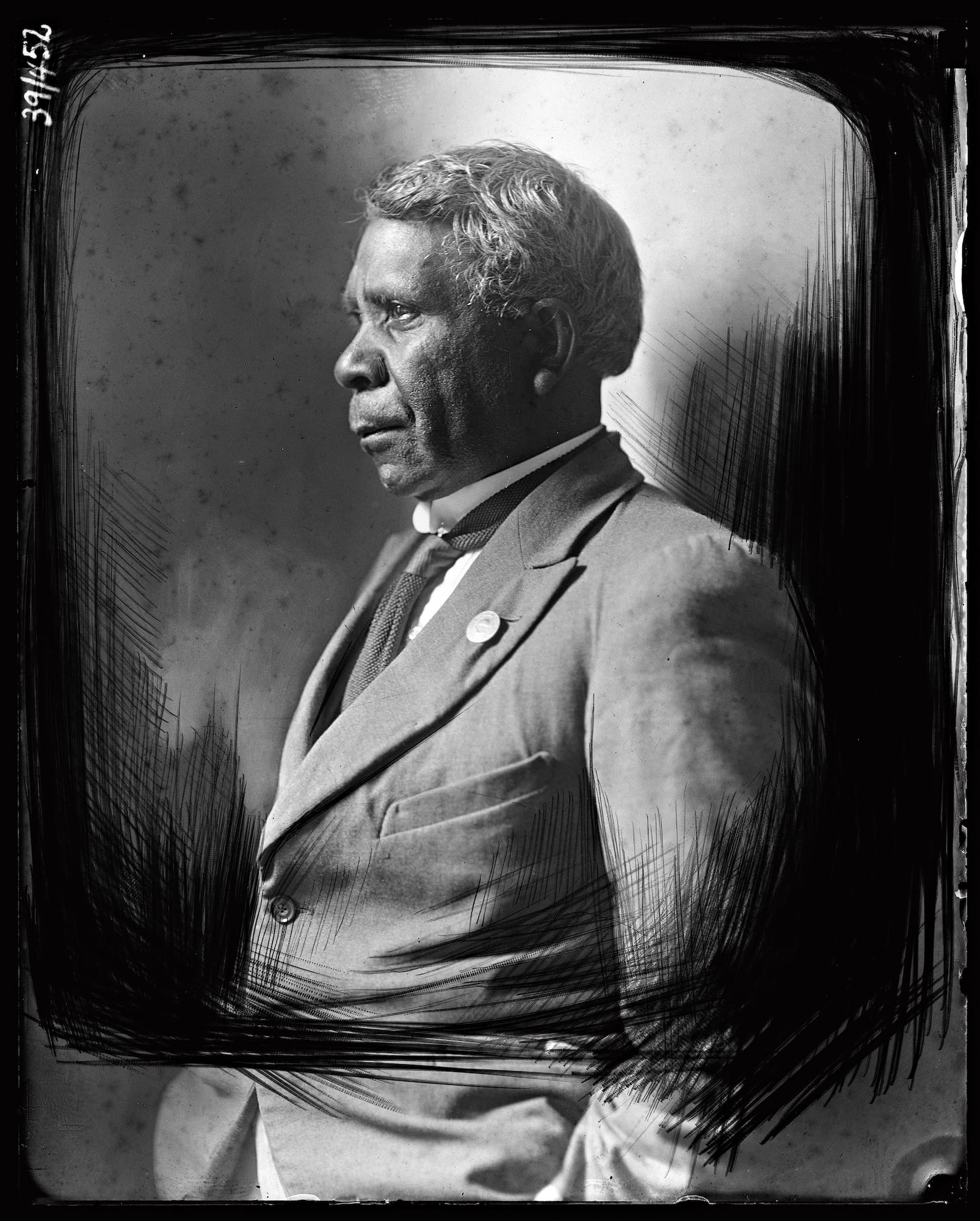

Celebrating the life of the brilliant inventor and activist David Unaipon.

Words Mark McGinness

PREACHER, author, activist and prodigious inventor, David Unaipon was a remarkable Australian. He braved the ignorance and prejudice of White Australia and, for decades in his quiet, scholarly, courtly way, he preached his truth and pursued an astonishing sweep of interests.

Unaipon was born on 28 September 1872 in a bark wurley on the banks of the lower Murray at the Point McLeay Mission in South Australia. He belonged to the Ngarrindjeri (“tribal constellation”), a confederation of some 18 tribal groups living in the region where the Murray River spills into lakes Alexandrina and Albert (Yarli). Where the saltwater meets the fresh, this was a sacred place.

He was the fourth of nine children of James Ngunaitponi (later anglicised to Unaipon) and his wife Nymbulda, both Yaraldi speakers from the region. David described his father as chief of the Warra Waldi tribe, living on the Jervois and Morphett estates near Tailem Bend where he hunted and fished in the lagoons. David’s mother was, he said, the daughter of Pullum (King Peter), chief of the Narrinyeri tribe.

According to Philip Jones in his authoritative entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, David’s father James was baptised in 1861 by the Scottish Free Church missionary James Reid as his first Christian convert. James took the cleric’s name and became one of the first Ngarrindjeri to read and write. After Reid drowned in Lake Albert, James came under the influence and protection of Congregationalist missionary George Taplin, who had chosen a traditional camping ground, Raukkan (“the Ancient Way”) for a settlement on the shores of Lake Alexandrina. It became the Point McLeay Mission, though it is now, again, known as Raukkan. James and Nymbulda’s was the first Christian wedding there.

The year before David’s birth, James was appointed the first Ngarrindjeri church deacon. He advocated for literacy and for years he undertook lengthy evangelical tours on foot to outlying Ngarrindjeri camps. James worked in the mission school as an assistant teacher – where all his surviving children attended – and he also worked as the school cook and librarian, and as a shepherd, boatman, labourer and rabbiter until he was forced to retire in the late 1880s due to ill health. He then relied on a small annual interest from his annuity. When the mission’s funds were embezzled in 1892, the authorities agreed to pay him an equivalent allowance.

David would later recall with affection the wurleys along the Murray where he once sat listening to the love song of the swans and to his elders telling tales and legends of his tribe. “I can almost smell the perfume of the burning gum leaves and see myself sitting in a canoe while my father snares wildfowl and fish. That life had a great charm for me and I have never wanted to shake off the association of my early ... days.”

His father’s Bible readings on the banks of the Murray had an enduring impact. His message? “Avoid greed and avarice and remain on good terms with all men.” David also loved reading sermons, particularly those of the American preacher Thomas De Witt Talmage (after whom David named his son) and Scottish evangelist Henry Drummond.

In 1885, after six years at school, Unaipon left to become a servant to Charles Burney Young, a prominent member of the Aborigines’ Friends’ Association. “I only wish the majority of white boys were as bright, intelligent, well-instructed and well-mannered, as the little fellow I am now taking charge of,” he wrote. Young encouraged the boy’s interest in philosophy, science and music while his wife introduced him to poetry, and Milton became an abiding favourite. (Later profiles of Unaipon would be headed “He preferred Milton to Shakespeare”.) An omnivorous reader, Unaipon also learned Latin and Greek and became absorbed in Sir Isaac Newton’s Laws of Physics.

Back at Point McLeay from 1890, Unaipon read widely, played the organ (Bach) and learned boot-making at the mission. In the late 1890s he took a job as storeman for G & R Wills, an Adelaide bootmaker, before returning to assist as book-keeper at the Point McLeay store.

On 4 January 1902 at Point McLeay he married Katherine Carter, née Sumner, a Tangani woman (another daughter of a chief) from Salt Creek in the Coorong. Unaipon referred in one report to a “restricted courtship”, and a few sources suggest it was an unhappy marriage. The couple had a son and daughter.

Unaipon’s boundless curiosity included a fascination for perpetual motion. Influenced by Newton, in 1907 Unaipon converted curvilinear motion into a straight-line movement and invented the hinge that drives modern sheep shears. His ingenious device converted the formerly circular motion of the cutting blade into a more efficient horizontal motion. He patented the concept in 1909 but lacked the funds to develop it. It was stolen from him and widely adopted. It still forms the basis of the operation of modern mechanical shears, yet he received

no money or credit for it.

Incredibly, he described the principle of the helicopter before it was invented. In 1914, he wrote: “An aeroplane can be manufactured that will rise straight into the air from the ground by application of the boomerang principle ... the boomerang is shaped to rise in the air according to the velocity with which it is propelled, and so can an aeroplane. This class of flying machine can also be carried on board ship, the immense advantages of which are obvious.”

Several experiments in vertical take-off had already been made but the first helicopter to manage a sustained flight was not until 1930, when Corradino D’Ascanio’s coaxial prototype took off at Rome’s Ciampino Airport using the principle Unaipon had foreseen. This led at the time to descriptions of him – some genuine, some jibing – as “the Aboriginal da Vinci”.

Between 1909 and 1944 he made patent applications for some 19 other inventions, including a centrifugal motor, a multi-radial wheel and a mechanical propulsion device, but the patents lapsed.

Unaipon’s seminal Myths and Legends of the Australian Aboriginals should have been published under his name. Instead, it was attributed to William Ramsay Smith, the chief medical officer of South Australia, on publication in 1930. Unaipon’s name does not appear anywhere in the book, except where he is mentioned in passing as a “narrator”, so the acclaim of being Australia’s first published Aboriginal author was denied him.

Among the legends in his book were animal stories in the mould of Aesop, Kipling and the Brothers Grimm: How the Tortoise Got His Shell; Why Frogs Jump Into the Water; Why All The Animals Peck at the Selfish Owl; and How Teddy Lost His Tail.

As Professor Adam Shoemaker observed in his Black Words, White Page: Aboriginal Literature 1929-1988: “All of Unaipon’s writing is fascinating, complex, and almost defies classification.” He also points out “it becomes clear that [Unaipon’s] story-telling is uneven, inconsistent, and is frequently fraught with tension between the Aboriginal and white Christian worlds”.

Shoemaker concludes, however: “It illustrates the honest response of a brilliant Aboriginal man to the pressures and expectations of the mission system. It portrays the paradox of a man moving away from traditional Aboriginal society while he ostensibly celebrates narrative and mythical elements of that society in his writing. It shows in a very clear and telling way the potential of the assimilation doctrine (especially when bolstered with the allure of Christianity), which was to be so comprehensively applied in Australia many years after ... His literary shortcomings presage some of the successes and destructive consequences of assimilation.

“Finally, at the time when full-blooded Aborigines were commonly believed to be dying out, Unaipon’s work exemplified an inventiveness, a vigour and a vibrancy which paralleled those qualities in his personal life. For all these reasons, the writings of David Unaipon deserve to be collected and re-published in toto.”

Finally, in 2001, Melbourne University Press published David Unaipon’s work as Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines, edited by Professor Stephen Muecke with an introduction by Shoemaker.

Unaipon encountered discrimination throughout his life. He recalled in his 1954 memoir, My Life Story: “In various places of the Bible I found the blackfellow playing a part in life’s programme ... In this Book I learned that God made all the nations of one blood and that in Jesus Christ colour and racial distinction disappeared. This helped me many times when I was refused accommodation because of my colour and race.”

In 1926, when he returned to Raukkan to see his family, he was abruptly arrested and imprisoned on the charge of vagrancy, despite producing both a five-pound note and his purpose for travel as self-defence. This insult was somewhat tempered a decade later by an invitation to a “levee” at Government House in Adelaide by Governor Sir Winston Dugan, and finally avenged in 1995 by Unaipon’s appearance on the $50 note. In 1953, along with other distinguished subjects of the Empire, he received a Coronation Medal to mark the crowning of Elizabeth II.

As a leading representative of his people, Unaipon assumed a public role as an advocate. In 1926, he appeared before a royal commission into the treatment of Aborigines and he advocated for a model Aboriginal state – a separate territory for

Aborigines in central and northern Australia. In 1928-29, he assisted the Bleakley inquiry into Aboriginal welfare.

In 1934, he urged the Commonwealth to take over Aboriginal affairs and proposed that South Australia’s chief protector of Aborigines be replaced by an independent board.

Despite a lifetime of activism, his preference for gradual change brought him into conflict with some of his peers over their proposal for a National Day of Mourning on Australia Day, 1938.

Unaipon continued to travel on foot, as his father had, in Adelaide and through country centres. He was still preaching at 87. He died on 7 February 1967. Philip Jones noted, “In his nineties he worked on his inventions at Point McLeay, convinced that he was close to discovering the secret of perpetual motion.”

Due recognition came slowly and, apart from that genial, noble image on the $50 note, there is also the David Unaipon Award for emerging Aboriginal writers and the annual Unaipon Lecture, both established in 1988; and, at the University of South Australia, the Unaipon School and its successor, the David Unaipon College of Indigenous Education and Research (1996-2015).

Poignant recognition came in 2004 with Unaipon, a magnificent tribute in dance by Frances Ring for the groundbreaking Bangarra Dance Theatre. It was a fitting homage to the man who was fascinated by perpetual motion, and whose spirit walked between two worlds with such dignity and grace.