No-one captured the Australian landscape with the exhilaration of John Olsen, writes Galah's obituarist Mark McGinness.

When John Olsen died last year at the age of 95, Australia lost one of its greatest artists. With Sidney Nolan, Fred Williams, Albert Namatjira, Russell Drysdale and William Robinson, he stands among the masters who have captured Australia’s wondrous landscape.

Over seven decades Olsen crossed the nation, blessing it with his brushes: from Sydney Harbour to Lake Eyre, from Bondi to Bowral to Broome, from Cottles Bridge to Clarendon, from the Murrumbidgee to Minderoo.

His exhilaration is best summed up in one of his most celebrated landscape series, The You Beaut Country, in the 1960s. His Australia was bursting with life and incident. A major Olsen retrospective in 1990 had the critic Elwyn Lynn hail the “wonderful cavorting of hills, creatures, rivers, lakes and roadways in Olsen’s sun-drenched optimistic extravaganzas”.

John Henry Olsen was born on 21 January 1928 in Newcastle, the older of two children. His father, Henry, was a clothes buyer; his mother, Esma (nee McCubbin) worked from home as a tailor. Life was grim; his father, a veteran, was damaged by the Great War. Before John turned two the country,

the world, was in the grip of the Great Depression. The desire to express himself was there from the beginning. In a house devoid of literature or art, young John drew on his mother’s cookbooks.

Educated by the Marists at St Joseph’s in Hunters Hill, he began his formal art studies at the Dattilo Rubbo Art School in Sydney in 1947, aged 19. From 1950 he studied at the Julian Ashton School under the Cézannesque painter John Passmore, whom he regarded as his artistic father.

Passmore’s psychological approach to drawing as a process of exploration and his adage “it’s not what you see but what you know” had resonance for Olsen. Time at the East Sydney Technical College (now the National Art School) with Godfrey Miller followed. While studying, he also worked as a freelance cartoonist and as a janitor.

After art school, he was influenced heavily by the work of French post-war abstractionists, the Italian modernists, and time spent with a group of young artists in Melbourne. This was evident in his first solo exhibition in 1955 and the group exhibition, Direction 1, the following year.

Between 1957 and 1960, with the help of a benefactor, Robert Shaw, Olsen visited London and Paris before settling on Mallorca. There, outside Deià, he absorbed the culture and cuisine of the Mediterranean, developing a more organic approach to his work and an intensifying interest in the dynamics of line. On his return to Sydney in 1960, he painted the exceptional “memory-journey” landscape Spanish encounter, channelling his Spanish village experiences into Sydney’s city life. This was immediately seen as a turning point in Australian art by the Art Gallery of New South Wales, which bought it.

His You Beaut Country paintings were inspired by a sojourn in the mining town of Hill End in 1960, where “I could feel Australia … I found myself saying how ‘beaut’ everything was”. Art critic Christopher Heathcote proclaimed, “Never again was the countryside to be a bleak wasteland, for Olsen discovered a ruddy beauty in the flickering emerald of flies swarming over wallaby droppings … the unaffected vitality of the landscape.”

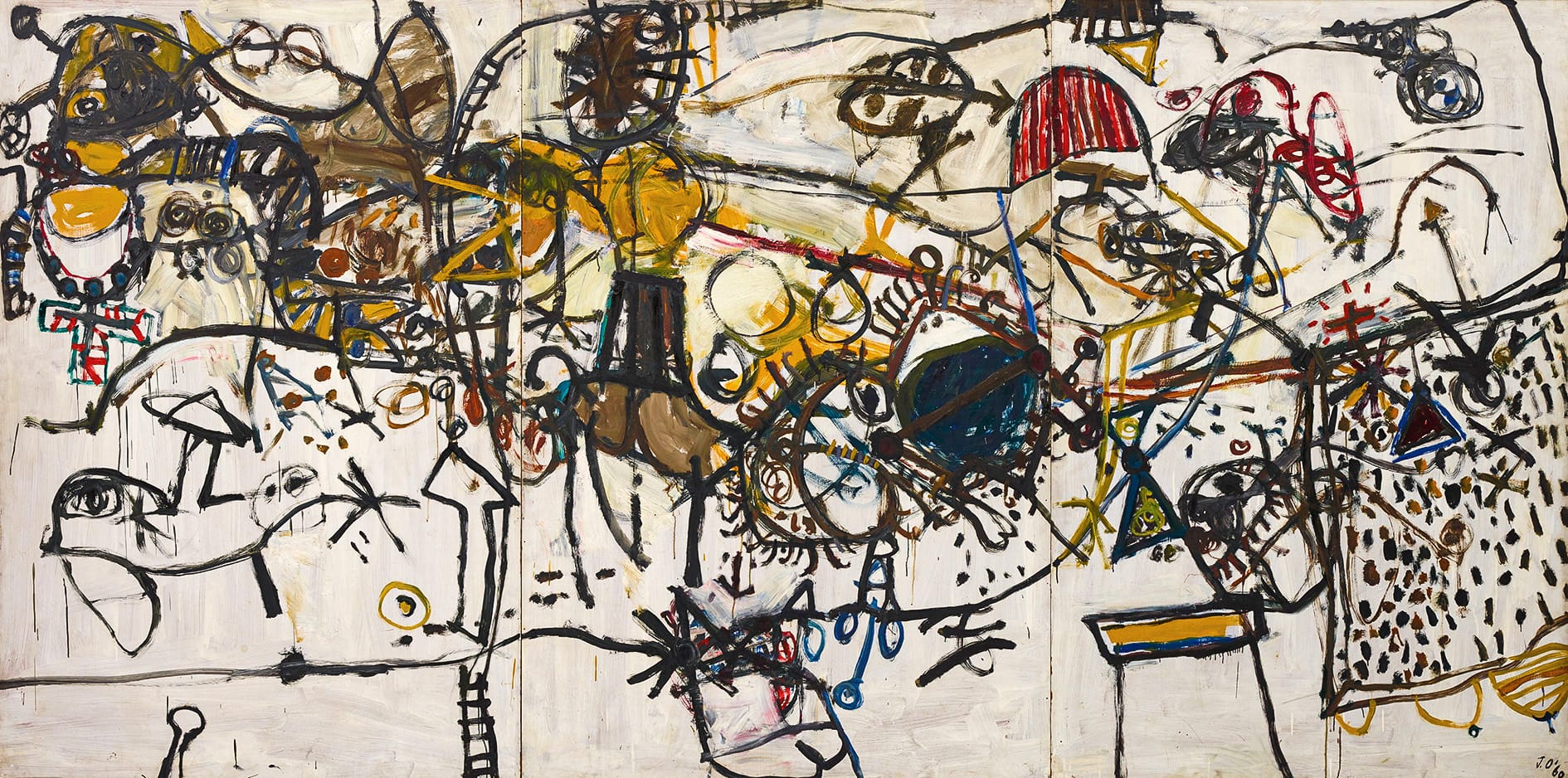

In the ’60s, when Olsen was probably at his most brilliant, he produced a series of ceiling paintings for private patrons: You Beaut Country, commissioned by art dealer Frank McDonald; Darlinghurst Cats and Sea Sun and Five Bells for collector Ann Lewis; and Life Burst commissioned by gallerist Thelma Clune. The most celebrated of these was the three-panel life-enhancing Sydney Sun (1965). In Olsen’s words, an “all-at-once world; a totality of experience”.

After two years in Portugal, he returned to Sydney where, in 1968, he established the Bakery Art School. Teaching and socialising took up much of his prodigious energy. At the end of that year, he took his family to Clifton Pugh’s property, Dunmoochin, at Cottles Bridge in rural Victoria. Here he immersed himself in painting outdoors in the open Australian landscape – sometimes in the company of other artists, among them Clifton Pugh, Fred Williams and Albert Tucker. Pied Beauty and The Chasing Bird Landscape from this time reflect a quieter, more meditative mood.

His closest primary contact with the Australian natural world came in 1971 when he joined a film crew developing a documentary series called Wild Australia. Ever after, birds, fish and frogs became features. Frogs, especially, became almost a signature of his work; and yet no two frogs were ever the same. One of his best was The Tree Frog (1973) capturing a sense of spontaneous energy. He loved them for their “careful awkwardness, an interesting kind of human thing going on, extended fingers, legs going everywhere when they swim and some even bask in the sun”.

In the early ’70s he was commissioned to paint a mural for the Sydney Opera House. Jørn Utzon had urged him to create a work that would “become part of the harbour”. The result was his masterpiece, Salute to Five Bells (1973). Inspired by Kenneth Slessor’s poem, this work spanning 21 metres features symbols, sea creatures and landmarks floating on a harbour of purples and blues. When it was unveiled by the late Queen Elizabeth in the Opera House foyer in 1973, Prince Philip (of course) asked him, “Where’s Luna Park?”

When Olsen first visited Lake Eyre in October 1974, it was only the second time it had been full since European occupation. He found it teeming with life – no longer the “dead heart”. There were birds, fish, insects; but as he returned during the next five years he saw the lake and all that life disappear. Influenced by Zen and Tao, he came to see the lake as “the void” as the vast Simpson Desert swallowed it up.

Here was a new lyrical view of country. Olsen scholar and Australian art curator Dr Deborah Hart believes his works on paper at about this time – Owls over a Drying River (1980) and The Rookery (1978) – “are among the most beautiful watercolours produced in this country”.

In the 1980s he lived on and recreated the plains of Wagga Wagga and then, for seven years, in the hamlet of Clarendon, South Australia. The glorious Golden summer, Clarendon (1983) is the fruit of that time. His oil washes on large canvases and the output of his travels through remote north-west Australia were widely praised. During the next 20 years Olsen painted from memory and visited and absorbed new parts of the country, including landscapes of the Northern Territory.

In 1999 he moved with his fourth wife to a farm outside Bowral in the Southern Highlands and continued to paint and exhibit until his death.

The advantage of a very long life is that the art establishment eventually recognises genius. Olsen had won the Wynne Prize in 1969 (The Chasing Bird Landscape) and 1985 (A Road to Clarendon: Autumn) and the Sulman Prize in 1989 (Don Quixote enters the inn). He was honoured as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (1977) and an Officer of the Order of Australia (2001).

And probably most satisfying of all, the Archibald Prize he had long coveted came at last in 2005 – half a century after he had protested as a student at William Dargie’s repeated success – with Self-portrait: Janus-faced. In 1990, when he had run a close second, he had famously dismissed the Archibald as “a chook raffle”.

But here he was, older, wiser, as Janus – facing mortality and disappearing into the landscape.

At 77, he was the oldest artist to win the prize. He wrote, “Janus had the ability to look backwards and forwards and when you get to my age you have a hell of a lot to think about.”

His extraordinary passion for art and life meant a turbulent existence off-canvas. In 1949, he married teacher Mary Flower, later a lawyer and civil libertarian. Their daughter Jane (“a little sibling of the brush”) was born in 1953. In 1962, after he had divorced Mary, he married fellow artist, Valerie Strong. That marriage ended in 1980 when he went to Adelaide to live with artist Noela Hjorth, whom he wed in 1986. That union endured for another year. In 1989 he married Katharine Howard, his wife until her death in 2016.

Olsen’s daughter Jane died in 2009, aged 56. He is survived by his two children with Valerie: their gallerist son, Tim, author of the searingly honest memoir Son of the Brush (2020); and Louise, an artist and designer.

John McDonald, one of Olsen’s most eloquent critics, has written, “One sees Olsen as a man of contradictions, almost bipolar in his swings between generosity and selfishness, grandeur and pettiness, self-confidence and insecurity. In pursuit of his muse, he has been monstrous to those closest to him, then felt racked with guilt … Those who know him best have shown they will forgive almost anything.”

He continued to paint until the end. In September 2022, he ventured again to Central Australia and was almost felled by a chest infection. Back home in Bowral a few weeks before his death, he was cheerfully working on a large canvas.

The last words must be his: “To be an Australian landscape painter is to be an explorer. There is so much to look at and observe about the Australian landscape, how it varies from tropical to the coastal fringe, and the interior. It’s so multiple.

It’s a beautiful animal, that landscape.”