For years, Aunty Barb Nicholson has sat with Aboriginal prison inmates, listening to their stories. As the 12th volume of their poetry is published, she reflects on a project that has changed lives.

Words Ryan Butta

Photography Rachael Tagg

Galah is highlighting remarkable community work in rural and regional Australia in a series made possible by our partnership with Westfund, a not-for-profit health fund with a 140-year history in rural Australia.

IN the early 1980s, Aunty Barb Nicholson was living in a small town outside

Newcastle, New South Wales. She describes it as a place where “you had to be there for five years before anyone nodded hello to you, and 10 years before they knew your name.”

Unemployed, recently separated and grieving the loss of her mother, she needed to make a change. Approaching her 50th birthday, she thought, “I’ve got to go to work or I’ve got to go to school, or I’ll go mad.”

One day, one of the few friends she had made in town invited her to take a trip. The pair ended up at the University of Newcastle, where Aunty Barb followed her friend down a long, dark corridor. Before she knew what was happening, Aunty Barb was pushed through a door. As she heard the door close behind her, she realised she had walked straight into a trap. A trap that would alter the course of her life.

I meet Aunty Barb at her house in Port Kembla, not far from where she was born and raised on the Aboriginal reserve at Kemblawarra in the Depression years of the 1930s. Port Kembla is Wadi Wadi country and Aunty Barb is a Wadi Wadi elder.

The house sits on a sloping block, stairs leading up to the front door. Any questions I have about how the 89-year-old navigates the steps each day are dispelled when Aunty Barb comes to the door. She is all energy and verve. Inside, the

walls are lined with Indigenous art; a carved wooden snake guards the door through to the kitchen. Her TV cabinet is stacked high with DVDs and CDs. Neil Diamond’s Love at the Greek occupies a prominent place.

Aunty Barb laughs about the “trap” set for her all those years ago: she left the university that day enrolled in the Open Foundation course for mature-age students. The trap was her friend’s response to Aunty Barb’s “whinging about wanting to go back to school”.

Eventually, Aunty Barb graduated with an arts degree: a triple major in English literature, philosophy and linguistics. Not satisfied, she moved to Sydney and took up a position at the University of New South Wales, where she completed a master’s degree.

Education for Aunty Barb felt akin to being reborn. “It was like peeling the fish scales off my eyes,” she says. “A lot of the stuff you learn you relate to, because things you might’ve experienced, that made you uncomfortable, suddenly, somehow you can see why it happened. Education gives you the ‘why’ that happened and ‘how’ that happened.”

It was during her time in Sydney that Aunty Barb started working on the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Watch Committee, an organisation monitoring the treatment of Aboriginal people in police and justice custody. As a committee member, she would sometimes be the first person called in the

case of a death. She describes the work as hard, and her face pinches as she recalls.

During her eight years on the committee, her role was to represent the families. “That is the prime thing: you are representing the family,” she says. “The family can’t always be there, but you’re dealing with the governor and you’re dealing with the relevant authorities, from the Minister for Corrective Services to the racist redneck guard.

“There was never a time when it wasn’t traumatic,” she says. “You’re dealing with the families of people who died in custody and there are no answers. And they’re getting the runaround from authorities. They’re not getting anything.”

At the same time, Aunty Barb was also heavily involved in advocating for the Stolen Generations. She has no regrets, but smiles ruefully at the memory. “I had to pick the two hardest things.”

After several years in Sydney, Aunty Barb felt the pull of her hometown and decided to move back to Port Kembla. Her idea was to retire, but in reality she was only just getting started.

After arriving home, she was approached by the University of Wollongong. Would she be at all interested in taking up a lectureship in Aboriginal Studies? “It wasn’t my discipline, and I was really nervous about that. But philosophy teaches you a lot of good things. You don’t always get better at philosophy, but it makes you better at everything else.”

The contract was for one year, but Aunty Barb is still attached to the university today, delivering occasional interdisciplinary guest lectures on subjects ranging from land rights to criminal justice. The university recognised her work in law studies in 2014, awarding her an honorary Doctor of Laws.

I ask Aunty Barb if she would describe herself as an academic or an activist. She is unimpressed with the question. “Take your pick,” she says. “I don’t describe myself. Other people are good at that, putting descriptions on me.”

I decide to ascribe neither label. She defies definition; any label seems too small to encompass the work she does, any title too limiting to describe the things she has achieved. There is a restlessness to Aunty Barb, a desire to do more, that saw her take up another challenge at a time in life when most are not winding down, but have indeed wound down.

Aunty Barbara Nicholson, editor of 12 volumes of Dreaming Inside, hopes the project will “change lives and change minds”. Photography by Rachael Tagg.

In 2011, Aunty Barb took part in a Write Around the Murray tour, which took writing workshops to the communities of the Murray River. She insisted on including a stop at the Junee prison to run a workshop for its Indigenous inmates. “We did some readings, which the lads were not one bit interested in at all,” she recalls.

But a year later, the prison invited Aunty Barb back to repeat the workshop during NAIDOC Week. She gathered a small team of writers including Dark Emu and Black Duck author Bruce Pascoe (more in the story Almost French in Issue 10) and, with some funding from the South Coast Writers’ Centre, made the five-hour trip back to Junee.

“We didn’t know what the hell we were doing,” Aunty Barb tells me. “We had absolutely no plans, no methodologies, nothing put in place – just this mob going down there. I look back on it now and think, oh god. But from little things, big things grow. And from that first trip, we got that first book happening.”

The book, Dreaming Inside: Voices from Junee Correctional Centre Volume 1, was just 38 pages and contained the stories and poetry of six inmates. But big things did grow, and in May this year Aunty Barb and her team released the 12th volume of Dreaming Inside, containing the words of 127 inmates including, for the first time from Junee Correctional Centre, three female voices.

Since those first uncertain days, Ngana Barangarai (Black Wallaby), as the project is now known, has worked with hundreds of inmates and over a thousand poems, lyrics, memoir and philosophical observations.

Last year, Aunty Barb and the team took the project to the Dillwynia Women’s Correctional Centre near Windsor on Sydney’s north-west outskirts, and

published the Sista’s Green Sea Dreaming book.

Aunty Barb knows her work is producing more than just words and numbers and volumes for the inmates who attend her twice-yearly writing workshops. “It is so therapeutic for them. What they’ve got is a platform where they’re totally unjudged. They’re in an environment while we’re there that is culturally safe, and they are totally unjudged. That doesn’t happen in jails.

“It’s cathartic. So, for the first time, they can spill out in their voice, their words, what they want to say – not what some solicitor wanted them to say, or what some judge demanded. What they write is the backstory of all the offences they’re in there for.”

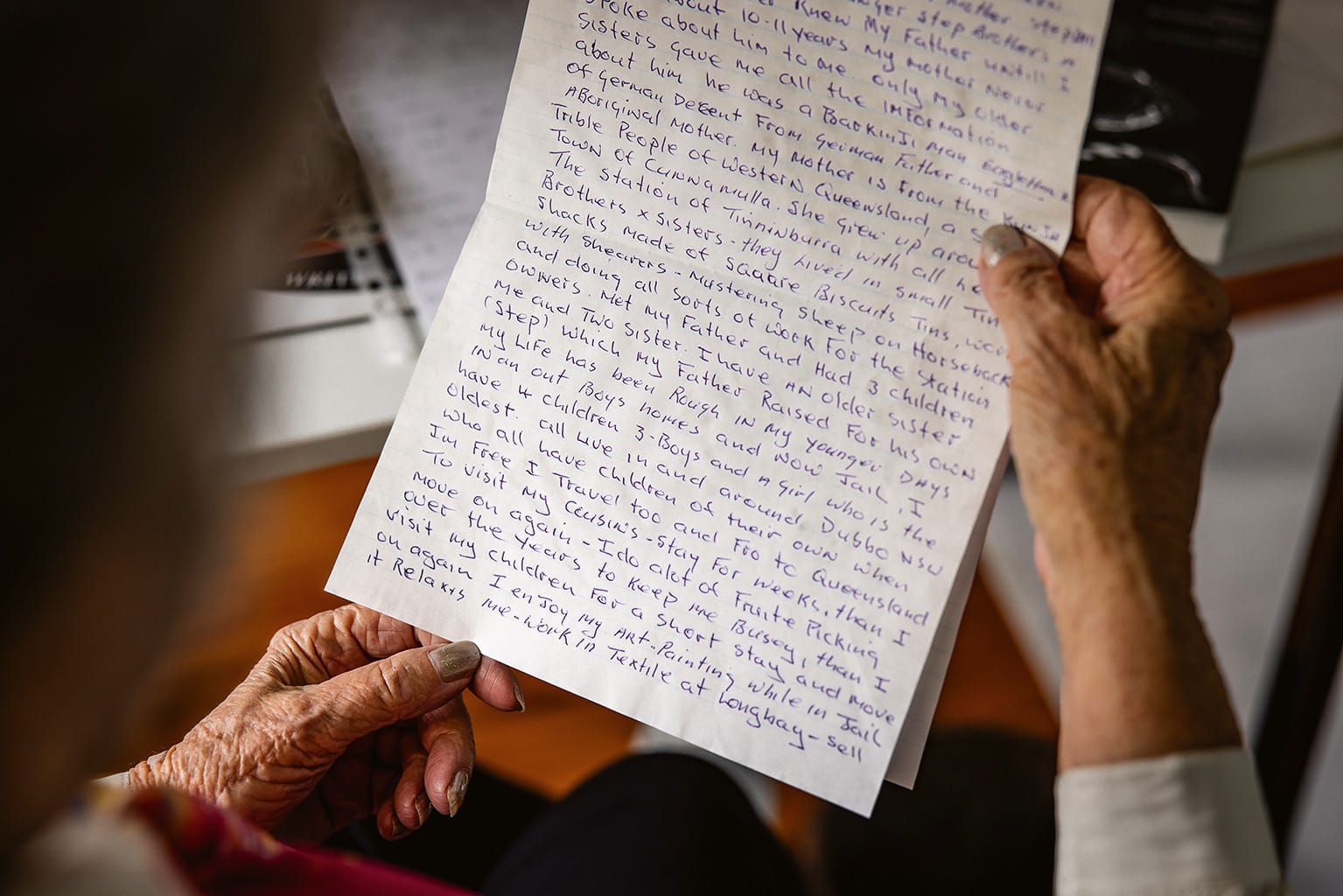

For Aunty Barb, it’s crucial that the words on the pages of Dreaming Inside are true to the men and women who write them, untouched by editorial tinkering. “We provide a place for them to tell their story in their words with all their bad spelling and with all their poor grammar, lack of education. They tell their stories. It’s their voices. I don’t interfere with their spelling or grammar or whatever.

“It’s their voice. And they have a right to have their voice. When you start tinkering with it, you are judging.”

Like any creator who releases their work into the world, Aunty Barb harbours secret desires for its path in life. She would like Dreaming Inside to be a work that changes lives and changes minds.

“I think if the legal profession, the judiciary, the constabulary all read these books, heard these stories and engaged with them, then it might make a lot of difference to the way the legal processes are handled and the strategies that are put in place for handling people.”

As I’m preparing to leave, Aunty Barb tells me of her plans for the upcoming book

tour, her appearances at the Brisbane Writers Festival and the BAD Sydney Crime Writers Festival in September, her next workshop at the Junee prison in October and her hopes for volume 13 of Dreaming Inside.

I wonder how she does it. How a life of activism, of confronting injustices, of placing her life in the service of others has not worn her down.

In fact, the opposite seems to have happened. The difficulties and setbacks Aunty Barb has faced have only served as a whetstone, honing her edge.

Aunty Barb has her own philosophy to explain the paths that her life has taken. “I think when you get born, you’ve got a ticket on your head that says: this person is going to do this.”

Dreaming Inside, Voices from Junee Correctional Centre Volume 12, edited by

Ngana Barangarai project director Aunty Barbara Nicholson, features the poems, lyrics and observations of 127 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander inmates. Buy online at southcoastwriters.org/shop