Poignant relics of domestic life are slip cast in porcelain, evoking tangible memories of those who used them and left them behind.

Words Annabel Crabb

I can remember clearly the first time I encountered Honor Freeman. I was wandering around the Sydney Contemporary Art Fair on its opening night in September 2017; my colleague Madeleine Hawcroft and I had just finished our backbreaking documentary series shot in Parliament House, and our treat to ourselves was to go to the art fair.

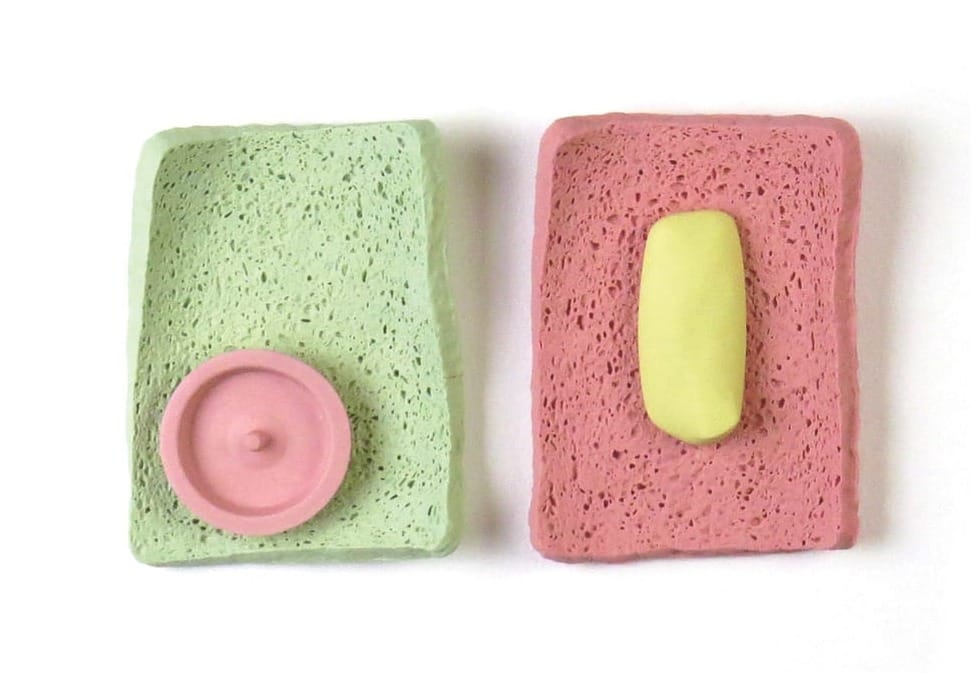

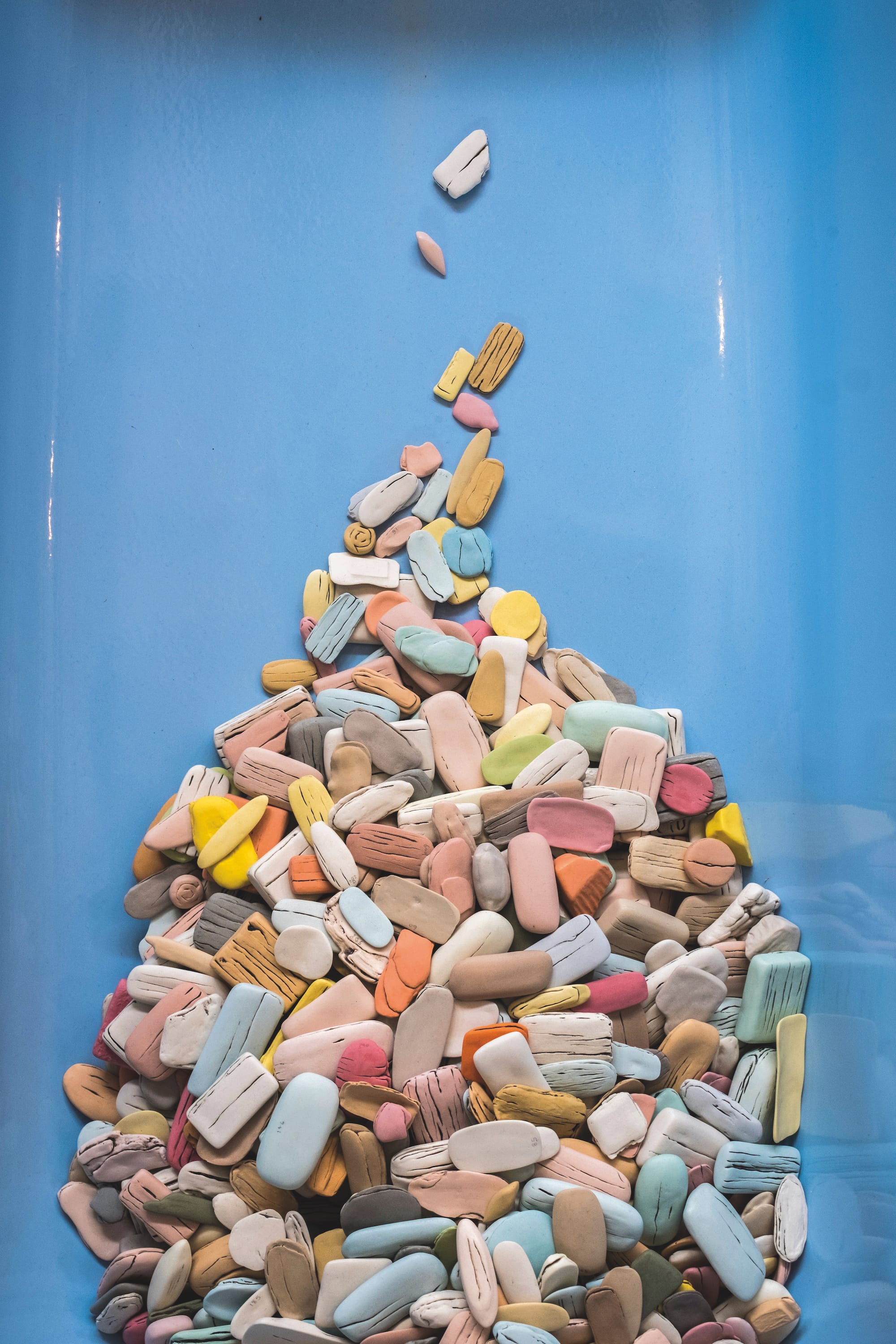

I stopped in front of a curiously beautiful work. It consisted of coloured, worn cakes of soap arranged on a board. It grabbed me in a deep, nostalgic way, because I remember cakes of soap looking like that when I was growing up on a farm in Adelaide Plains. Parched and cracked, with the suggestion of dirt in the cracks; this is what cakes of soap look like when they wind up in bathrooms and laundries where the water is hard and the hands are dirty. I couldn’t stop looking at it; it didn’t register right away that the soaps were porcelain, painstakingly slip cast and painted by the artist.

While I was completely absorbed, I became conscious that there was a woman standing next to me. She introduced herself and I apologised for being a bit vague. I explained that I was just utterly intrigued by this beautiful work in front of me.

‘I made it,’ she exclaimed. And it turned out we had a lot in common. Honor, too, had grown up in country South Australia. She was a mum juggling work and babies too. And she had been listening to Chat 10 Looks 3—the podcast I make with my friend and colleague Leigh Sales—while she worked in her studio making the soaps.

She told me the story of how they came about: a close friend’s elderly father had died suddenly. While the friend was packing up her dad’s stuff, she found herself overwhelmed by the discovery of a cracked bar of soap that her Dad had used every day, but wouldn’t again. A simple object, utterly unremarkable, and yet frozen permanently halfway through its banal life cycle. Suddenly, this humble object acquired intense emotional significance. So the friend asked Honor to cast this soap in porcelain for her. It was such a lovely idea and the resulting object was so beautiful that Honor continued to make these soaps again and again, later branching out into porcelain-rendered face washers and dried kitchen sponges.

I love the soaps and the other unremarkable household objects that Honor promotes into significance by casting them in the kingly medium of porcelain and investing her time and care (and sometimes filigrees of gold) in them. I think real lives and history are often contained in these objects that can seem so insignificant. And in my own life, when I look at the cracked bars of soap and compare them to the pump-packs of liquid soap that my own kids use in our city home, it makes me reflect on where I’m from and the things I need to explain to my children.

I bought a set of soaps and it hangs in pride of place in my dining room. Each soap is attached to the board with a magnet so that people can take them off and handle them; they feel smooth and heavy and packed with meaning. Leigh always comments on them when she’s at my house; her late father worked with his hands and there was always a cracked bar of soap at her home, so she feels the same connection.

I know that while Honor was making my soaps, her father died. The next time I saw her was at the Art Gallery of South Australia, at the opening of a new exhibition of hers in which she gently explored her own bereavement; a collection of grief’s accoutrements. Scrunched up hankies and tissues, all cast flawlessly in porcelain, plus a new collection of soaps, including one belonging to her dad.

It’s funny that her name is Honor, because I feel like she uses her profound skills to honour small things and uses them to tell a bigger story. She finds and coaxes the beauty out of the mundane. It’s the best kind of art.

honorfreeman.com; Honor is represented by Sabbia Gallery, Sydney sabbiagallery.com