Gardening in a drought-prone place of temperature extremes is not for the faint-hearted, but Jeremy Valentine loves a challenge. Here’s the latest instalment of In the Weeds, his monthly newsletter for Galah.

I'm not entirely sure where my obsession with rocks came from, and in particular, building things out of them.

Perhaps it was my English childhood, wandering the Cheshire countryside with its undulating tracery of dry-stone walls. As a child they held secrets: lost treasure, Roman coins, slow-worms, millipedes and snails. The many stiles allowing passage from one meadow to another mapped the made-up routes of walks with my dog.

They were glorious storybook times, that’s for sure.

When we arrived at The Stones 30 or so years later, it was immediately clear this was a place rich with rocks. Even before we entered the house grounds we could see the driveway, which traverses a long scarp of rock, reputedly excavated by a single man and his donkey.

As you might know from my previous musings, we’re perched on the end of the ancient lava flow of the (now extinct) volcano, Lalgambook (Mount Franklin).

During its last furious eruption, a great river of lava flowed down the valley along an ancient river bed, where it cooled over aeons to create a snaking lump of tessellated basalt.

It wasn't long before I was heaving barrowloads of lichen-gilded basalt into the garden, eager to replicate the many historic dry-stone walls in the district, a flight of steps, or a bollard where the vision granted.

And so the rock obsession began.

It suited me. I felt a strange affinity. It was as though I had developed pebbles for eyes.

These rocks, although not the easiest for building things because of their irregular and awkward shapes, are little worlds, or even planets in miniature. Upon them, nanoscopic gardens of mosses and lichens cling to their surface, while below there's a secret world of tiny creatures: spiders, prehistoric woodlice, the mechanical scuttle of giant centipedes, occasionally a snake.

It makes gathering them up an exercise in careful mindfulness.

I am mindful, too, not to harvest the rocks that make up the primordial pavements, whose lovely natural mosaics are still wonderfully intact. So only the ones lying on the surface are taken.

I fill the battered tray of the ute.

Different jobs require different rocks. For walls, a full combination of sizes is required. Generally the largest rocks form the foundations, but they’re also used throughout to anchor medium-sized ones, and to create visual interest. Small stones and rubble fill the gaps in the centre, with long cross stones to brace and strengthen, and flat stones for the tops.

It's my own trial-and-error formula that works with all the irregular shapes – a few basic common principles (of course), and a great deal of studying the old walls of the first settlers, which are now so much a feature of this part of the country.

For steps, the heaviest rocks with at least two flat sides are required. These specifications are most prevalent in the Ordovician sandstone, found in only a few spots here. These more elegant stones are a dream to work with, and I've made a mental note of each secret cache for future step projects.

At The Stones, where the historic buildings are homespun-built by Cornish miners with locally sourced materials, it's important to maintain their inherent humble code.

A garden wall too slick and polished at the hands of a showy professional would (in my mind) look way too smart and overly engineered in their midst. If a wall of rock can somehow look soft in the landscape, and at peace with the buildings, then this is the wall for this place. It's a balance I'm forever juggling.

We simply can't have the mockery of garden walls more clever than the house. So we are lucky that in order to keep things true to the spirit of place, we don't need to shoulder the financial cost of getting in the "professionals" – and the rocks, of course, are free. It's a win-win.

Luckiest of all is that a self-taught novice such as myself can quietly beaver away with a ratty pair of gloves, a mattock, and a bottomless quarry of determination.

Working with stone is a tonic for a busy mind. I cannot tell you how, under my apparent calm demeanour, there lies a virtual beehive of mental chaos. I spend most of my time juggling the worries of the world, the bombardment of creative ideas, the endless logistics of running our own business, and a brain full of words. Wrangling rocks seems to be one of the only things to quieten the mind. That, and gardening, of course.

In short, this is my own personalised version of meditation.

Built to protect and made to last, SÜK Workwear is for hard jobs, dirty days, and serious wear and tear.

July is generally a static time in the garden. It's the one true season that we can turn our back on tending to plants and funnel our energies into the structures and hard landscaping. It's one of my favourite times of the year when we can get the tough stuff done.

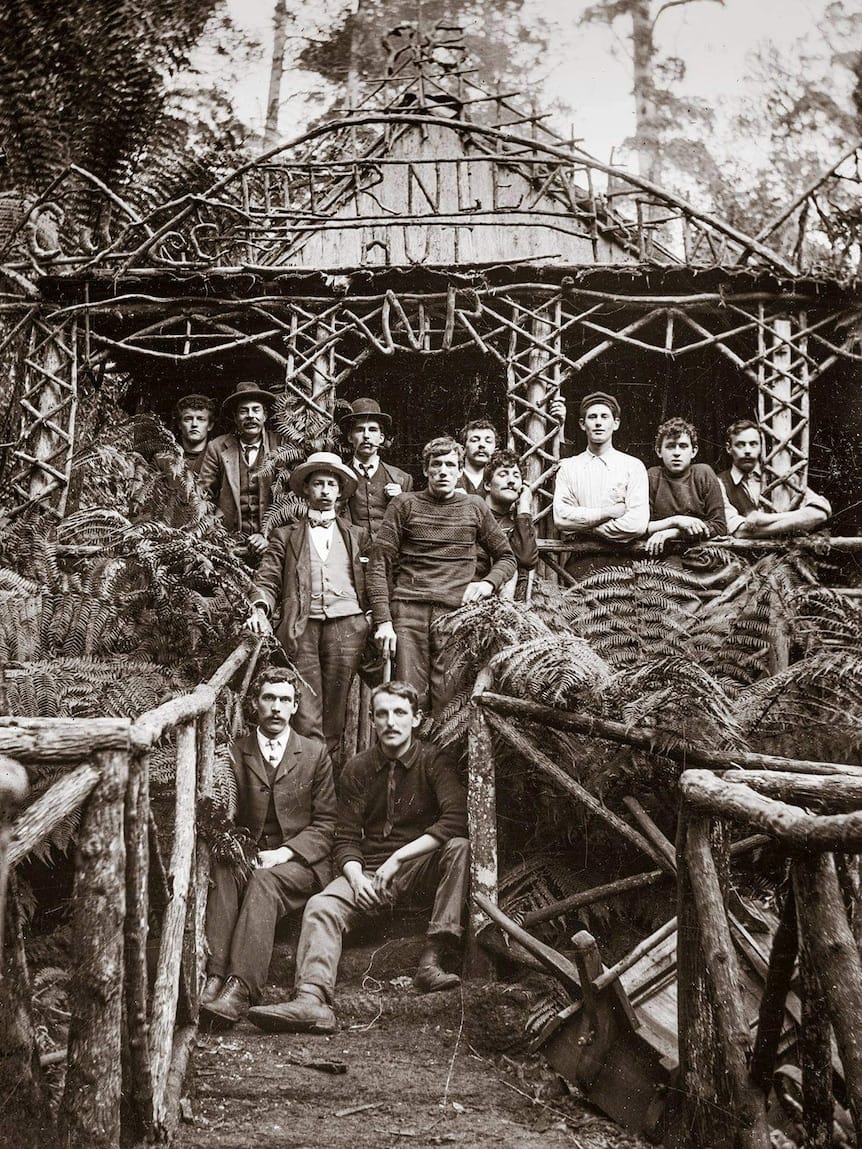

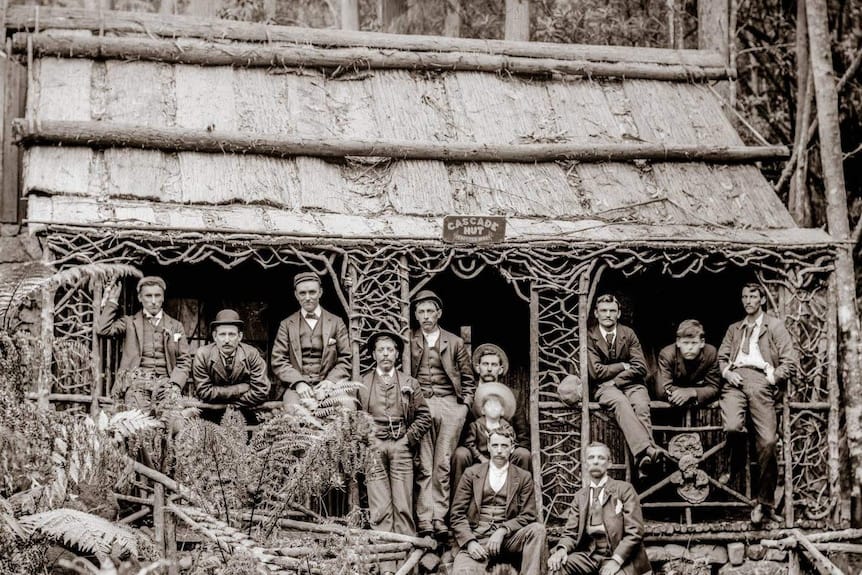

It's now that I dream up ridiculous plans of long Walling-style pergolas, ha-ha walls, and a rustic summer house akin to the lost huts of Kunanyi (Mount Wellington) in Hobart.

Images from Maria Grist's book The Huts of Kunanyi/Mount Wellington.

Catch up on Jeremy's previous stories here or find him on Instagram at @thestonescentralvictoria