Is ‘Made in Australia’ just misguided nationalism? A nice idea, but not an economic reality? GALAH discovers three Australian businesses that are trying to find out.

Words by Annabelle Hickson

WHEN Bede Aldridge finished a four-year saddlery apprenticeship, he was 22 years old, newly married and about to set up shop in the shed on a property in Crookwell, New South Wales, repairing shoes rather than making saddles, because the horse flu going around at the time meant no-one was ordering custom leather horse gear. He was one of the last apprentices to go through the saddlery scheme in Australia, and most of the saddlers he knew were 40 years older than him. It did not feel like a ‘growth’ industry.

His wife Jemima, who was getting her head around the new-to-her triumvirate of their long drop toilet, country life and motherhood, would ferry the shoes to and from town to help, but they were lean times, she says. When a master saddler in Dubbo offered Bede a full-time job, they jumped at it.

‘But it only lasted 18 months,’ says Jemima, explaining that the master saddler wanted to downsize. ‘Bede came home one day—I was pregnant with our third boy—and he said, “I don’t have a job anymore”. We’d just bought a tiny cottage with our meagre savings—saddlers didn’t earn much, just the basic award wage—and we were like, what now? All Bede had was his tools and our garage.’

Without any other options on the horizon, Bede painted the inside of the garage next to their cottage in the heart of Dubbo, put in glass doors and hung a sign on the gate saying ‘Saddle Maker’.

Bede’s former boss helped him out with job leads and for the next five years he built up a business making custom goods and saddlery for clients while Jemima looked after the children: she had four babies under five with another one on the way.

‘The customers would come through the gate, there’d be kids’ bikes all over the driveway and I’d be outside at the washing line with a baby on my hip,’ says Jemima.

Bede was doing what he loved, but it was hard to make enough money to support his growing family. He considered joining the police force, but the couple decided to give the saddlery business one more push before he became a full-time cop and a hobbyist saddler. It was around this time that Jemima asked Bede to make her a leather bag. She’d bought a bag from a chain shop and it fell apart; she knew Bede could make something beautiful that would last. So she sketched a design for a tote bag and he made it.

‘I took it down the street for coffee, and then suddenly we were getting people asking for the bags.’

The requests kept coming in and Bede realised he had a product that he could create a pattern for. Whereas before he had been making one-off pieces, struggling to accurately quote for this custom work, he and Jemima started imagining a range of products they could create patterns for: bags, belts, wallets. And if they had patterns for products, Bede could maximise production efficiency and teach other people how to make those products. Their business could grow beyond Bede’s one set of hands.

In 2014 the couple hired their first employee, a local upholsterer who Bede trained to use the leather sewing machines. She still works for them today. Then they received a $10,000 grant from the local council that gave them enough firepower to open up a workshop and retail shop in a street around the corner in 2016.

Today, Jemima and Bede sell a range of handmade leathergoods under their Saddler & Co brand. They run a tight ship, making sure their production is as efficient as possible. Jemima drives the marketing—they don’t manufacture for wholesale at all—and now online sales make up 60 per cent of their business. They have plans to open a retail store in a major city and significantly increase their online sales. What was once a one man show is now a business supporting 12 people and they’re starting to imagine what 20 people might look like.

A key part of their growth—other than Jemima’s marketing nous—has been Bede’s decision to start an in-house apprenticeship saddlery and leatherwork program. There’s no official saddlery apprenticeship scheme through TAFE anymore, so Bede devised his own. To grow, he needed more saddlers. To find more saddlers, he needed to train them.

‘I didn’t want people just to learn hobby skills. I wanted them to be at the top of their game; I wanted them to be able to do anything. If I can leave a legacy, I want it to be that all the best saddlers came from Saddler & Co. But with no TAFE, there was no ticket and I had to work out how to attract people to the business and somehow retain them for four years. So I created a training program, using the TAFE syllabus, but then applying the skills here in the workshop. There are five levels over five years, with checkpoints along the way.’

The in-house training scheme isn’t an official apprenticeship, so Bede and Jemima don’t get government subsidies and they must pay their trainees full-time wages rather than apprentice wages. And even though labour is their biggest cost, they choose to pay their trainees well above the minimum wage.

‘We can’t be paying people minimum wage. You can love what you do all you like, but eventually you’ll think, “I could get more money somewhere else”,’ says Bede, who finished his four-year trade on $415 a week. They have a long-term outlook and see the value in retaining skilled staff.

Bede and Jemima are passionate about making an Australian-made product because they want to continue the craft of saddlery here. But it’s not all nostalgia. They are also focused on creating a profitable business so they can train and pay their employees well.

Economist and director of the Centre for Future Work based at the Australia Institute, Dr Jim Stanford says it’s an urban myth that rich, high-wage countries can’t do manufacturing. He says this false belief, along with the complacency that a resource-rich country like Australia can afford to have, helps to explain why Australia has one of the most under-developed manufacturing sectors of any industrial country in the world.

‘The countries that are successful in manufacturing are competing on quality, innovation and value, not on cost,’ says Dr Stanford. ‘And the reason they are successful is because they can produce and sell things that are expensive. Countries that produce luxury cars are not competing on cost, they’re competing on something else. And they do it well.The success of Germany, Japan, Sweden, the Netherlands, even Korea—all countries with high and rising wages—is based on the ability of those national economies to produce high value–added products and to get them out into the world market.’ Dr Stanford explains that his interest in manufacturing is not based on a kind of nostalgia, but rather ‘the concrete, qualitative characteristics of manufacturing that explain why it is valuable’.

‘There’s no other sector in the economy that uses more innovation, R&D and advanced technology than manufacturing,’ he says. If you’ve got a strong manufacturing sector, then you’re going to have a strong innovation sector.

‘Manufacturing also has a very extensive supply chain, so that if you get a major facility in manufacturing, it’s not just the jobs in that facility that you’re getting, you’re getting jobs in all of the other industries that feed into it.’

More than 450 kilometres northeast of Bede and Jemima’s saddlery is a very different sort of manufacturing business. Over three hectares of sheds and workshops buzzing with a mix of robots and skilled tradies in the small town of Inverell, New South Wales, BOSS Engineering makes heavy-duty trailers, ute trays and large agricultural machinery.

‘Our product, no doubt, is more expensive than some imported products,’ says BOSS Engineering director Dan Ryan, ‘but, in turn, I think farmers recognise that they’re getting a product with a life cycle much longer than the imported products. They can access parts manufactured locally and they can actually ring and talk to an Australian engineer if they need to. We’ve found that if you listen and build the product that Australian farmers need, they’ll back you every day of the week.’

BOSS Engineering opened 15 years ago in Inverell, population 11,000, with an initial plan of making truck bodies. But the group immediately got side-tracked into building agricultural machinery for local farmers. Since then they have made more than a thousand planters—some as wide as 36 metres—which they send to farms across New South Wales, Victoria and, more recently, Western Australia. Their planters are built to suit Australia’s dry conditions—no tillage or minimum tillage—and they can plant through stubble from the previous crop, which Australian farmers like to leave in to preserve the soil structure and minimise moisture loss.

‘They’re also backpacker-proof,’ says Dan. ‘You can put a backpacker on it and he’s still going to do a great job without having a high level of expertise.’

From a team of 25 in the early days, they now employ 155 people. Every step of the manufacturing process is done in-house. BOSS is a major employer in the town and currently trains 19 apprentices across a range of trades.

BOSS Engineering is fastidious about running their workshop efficiently. The factory uses state-of-the-art equipment including 3D software, computer numerical controlled (CNC) machines and robot welders.

‘We know that we’re behind the eight ball here because of our high labour costs and our high input costs like electricity and steel prices, so we have to be very efficient at what we do,’ says Dan, ‘and that means having good equipment and having good, smart people.’

BOSS Engineering’s workshop is fully booked for the next 12 months and the future of the business looks bright.

‘We’ve got the best farmers in the world in Australia; agriculture is an exciting industry to be part of. We’re going to continue to grow and expand into new areas, keep improving our products and designing new products. That’s the plan,’ says Dan.

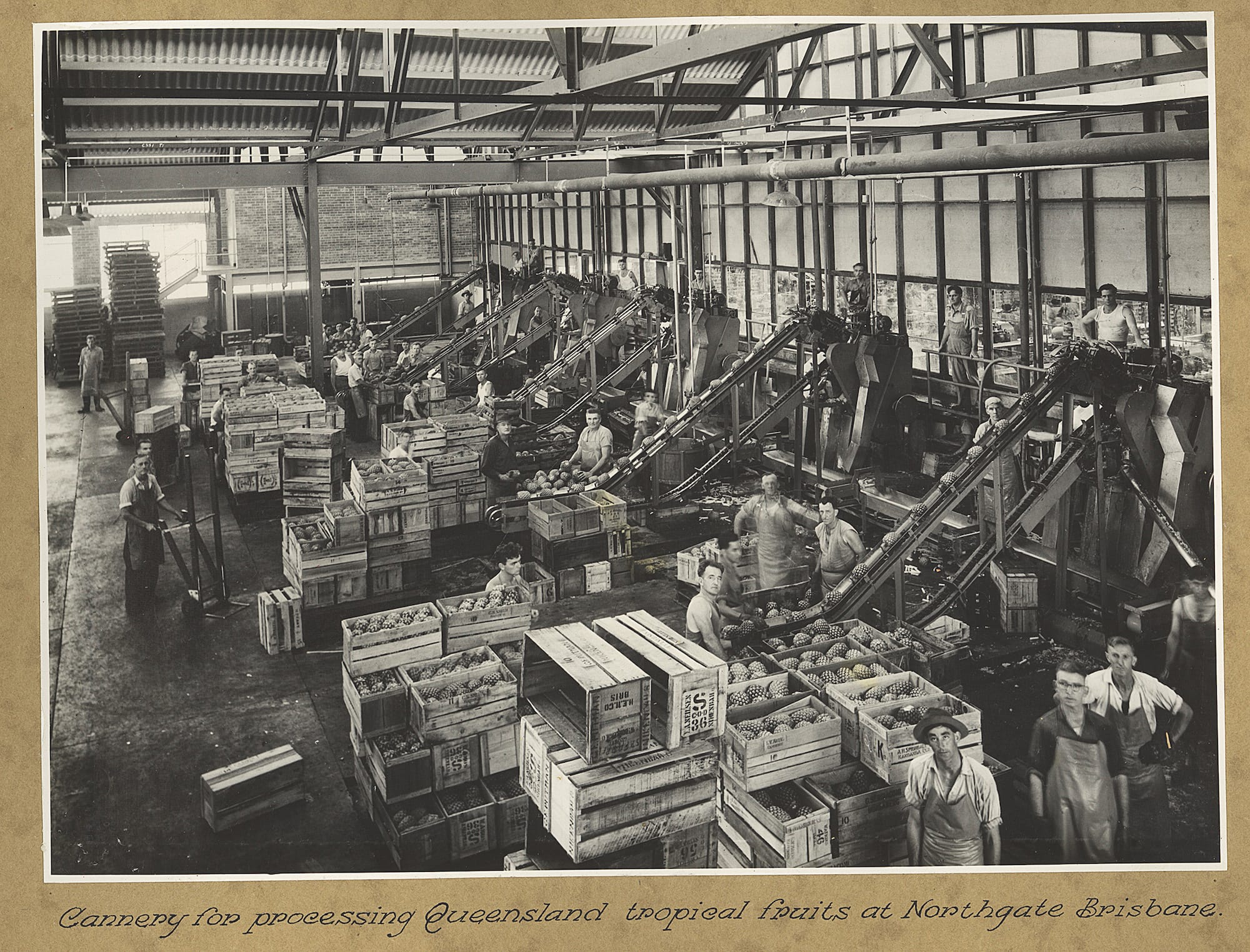

Further north in Toowoomba, Queensland, Colin Dorber wants to add value to Australian-grown fruits and vegetables, with ambitious plans to start building a new cooperatively owned state-of-the-art cannery and vegetable processing plant this year: the first new cannery to be built in Australia for 60 years.

In 2011, when Heinz decided to cut jobs at its Golden Circle cannery in Brisbane and shift beetroot production to New Zealand, beetroot growers in the Lockyer Valley were devastated. Colin knew it, because he lived there. It’s taken more than 10 years of writing business plans, research and attracting investors, but he is confident the Lockyer Valley Fruit & Vegetable Processing Company cannery will be profitable. The new processing plant won’t have to deal with the legacy inefficiencies of older factories. Everything has been designed with innovation and efficiency at the forefront.

‘Labour costs will be 15 per cent of total expenditure. Everyone says you can’t afford labour in Australia: not only can we afford it, we will pay above market rates. We can make a profit using Australian labour because it’s about mixing it with technology and giving people meaningful jobs. We don’t need people to push a barrel; we’ve got robots to do that.’

Colin believes manufacturing in Australia can compete internationally—even for inexpensive products like canned fruits and vegetables—as long as integrated innovation is adopted.

‘We have an innovation paper that runs for 56 pages and in it are four patentable products,’ he says. Some of the innovation is around creating by-products from vegetable waste, such as beetroot powder supplement for horses and greyhounds. Other innovation is around optimising production procedures and transporting produce in a way that minimises damage. The factory will make their own cans and be energy efficient.

The proof will be in the pudding. Colin has raised about $2 million of the $180 million needed for the project. He recently signed a 40-year lease (with an option to buy) on 54 hectares of land in the foothills of the Toowoomba mountains. The development application has almost been approved and Colin hopes to break ground this year.

He will need all the innovation and efficiencies he can get. Back at the Australia Institute, Dr Stanford points out that if you’re not selling something expensive, ‘you’re going to have a narrow base to compete on and there’s always going to be someone else in the world who’s willing to work for less’.

But Dr Stanford insists higher wages do not mean Australia can’t be a manufacturing powerhouse, citing the huge opportunity we have to develop minerals that will be needed in the renewable energy transition, such as lithium, into value-added manufacturing. If we can look beyond defeatis—‘our wages are so high and we are so far away’—and complacency—‘let’s just dig stuff out of the ground’—Australian manufacturing will boost innovation and feed businesses up and down the supply chain, playing a strategic role in the nation’s economy.

‘Manufacturing is a great way to try and address regional economic and social policy goals, including creating some good jobs in the region so that people who live there can have a future, rather than feeling they have to migrate to the city,’ says Dr Stanford. ‘The countries that have succeeded in world trade are not countries where the market determined what is called in economics their comparative advantage. They are countries that deliberately constructed a strong and beneficial foothold in key industries. They created their own advantage.’

Businesses like Saddler & Co, BOSS Engineering and (if all goes well) the Lockyer Valley Cannery have created their own advantage. It hasn’t always been easy, but for them Made in Australia is not just a nice idea, it’s an economically viable, exciting reality.

saddlerandco.com.au; bosseng.com.au; lvfvco.com.au