From their home in Kakadu National Park, artists Irene Henry and Harold Goodman channel a little of their own character into their creations.

Words Sam McCue

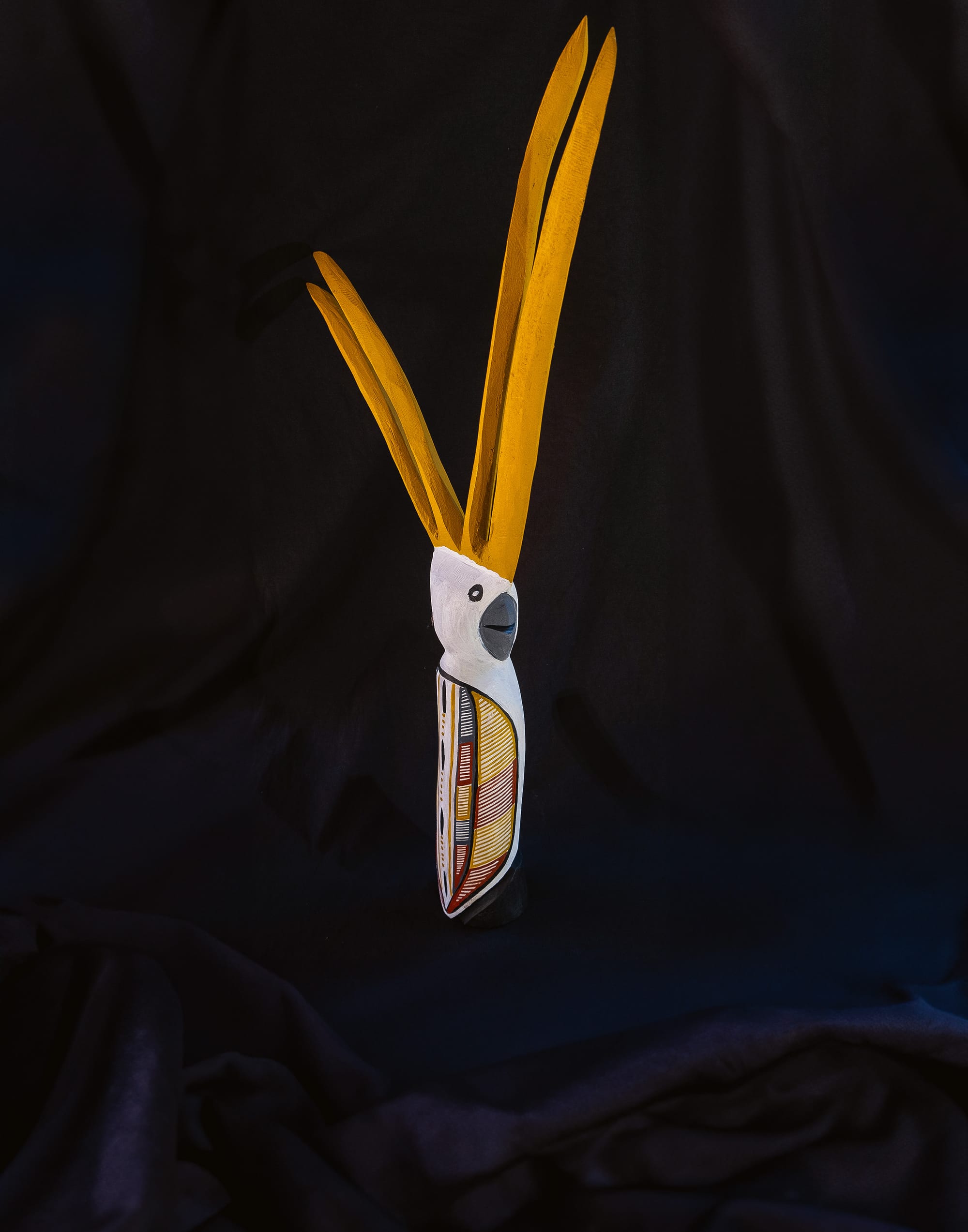

Stanley the white cockatoo is handsome and proud, with wise eyes,

a lop-sided grin and a dark yellow crest that’s almost half his height.

For a wood carving, he sure has personality.

Turkey bush and kapok are a blooming profusion of fuchsia and yellow as we drive past a paperbark-fringed billabong and into Kapalga Outstation. Here, inside Kakadu National Park, is the home of Irene Henry and Harold Goodman, and the birthplace of their whimsical birds.

Buyers across Australia and the world have fallen for their carved and painted sculptures—mainly bilarrkbilarrk (galahs), lurrilmal (black cockatoos) and ditjgan (white cockatoos)—each capturing a little of their makers’ spirit

and character.

“A lot of people ask me, ‘How do you do it?’” says Henry. “And I just say, it’s a gift.”

I first saw their work as part of the 2022 Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, the nation’s longest running Indigenous art awards. And, like thousands of others, I was captivated by Big Mob Karnamarr: a posse of seven black cockatoos, each with its own distinct personality and a flamboyant crest raised like fingers of flame. The work was selected as a finalist.

A few months later, the pair staged a sell-out exhibition at Darwin’s Laundry Gallery, a new outlet in a ’70s laundromat (motto: “old stories, new spin”). Gallery co-founder Nina Fitzgerald says the birds sold “like hot cakes” after the Ditjgan exhibition, named for the white cockatoo, was shared on social media. “The birds are so unique and are loved by everyone who sees them,” she says. “Almost 50 birds sold in a couple of days—insane.” The sculptures, now available through Laundry Gallery, have been bought by collectors in Switzerland, France, the UK, the US and Japan.

It’s a world away from Kapalga, a couple of hours’ drive east of Darwin,

where Henry and Goodman have lived since 1990. This modest cluster of buildings, once an outpost for the CSIRO and then Parks Australia, is home

to about 10 people, including Henry’s niece and sometime offsider, artist Rhonda Henry. The couple’s school-age grandchildren, Ailena and Felix, are also willing assistants.

When we visit, Henry and Goodman are ready to show us their process, starting with selecting the timber.

“We could go for a walk in the bush, but we have a buffalo hanging around,

so we have to be careful,” says Henry. “They can be so mean.”

Henry chooses from a jumble of Y-shaped branches, each about the thickness

of my forearm. “We peel the bark like this—oh, this one is too small.” She flakes away every shard of dry bark from the second piece of timber and hands it to Goodman. He has removed his red shirt and his red Sydney Swans cap—the couple are huge fans—and his angle-grinder is powered up. He’s ready to bring forth a bird.

It’s officially wurrkeng (cool weather season) here in the Top End, and a breeze is wafting through the open-sided shed where Goodman works beside his son’s old Holden. Outside, the dogs Tigerlily and Brownie lie in the sun.

“When we cut the wood and it has holes in it, we stick it in that pile,” says Henry, pointing to a pile of cut timber. “Then we use it for firewood.”

By now, though, having created hundreds of birds together since they began in earnest in 2018, these two are pretty good at choosing the right pieces of fallen timber, mostly stringybark and woollybutt.

“I tell him that’s the right one, and he cuts it,” explains Henry. “It’s hard with the saw, so we’re thinking of getting a chainsaw. We’ve gone through about

10 saws—every time we come to Darwin, we go to Bunnings! We take a saw

in the car back to Kapalga in case we see a [suitable] tree.”

Next, Goodman engineers the base. He slices away thin sections, testing, testing, testing—will the timber stand upright? This one is a tad top-heavy. “Nah, a bit more,” says Henry. “That’s it. See, now it’s standing.”

Carved and painted birds are a strong tradition in the Tiwi Islands, just

80 kilometres north of Darwin, where Henry has family. She attributes her painting skills to her sister, Aileen Henry, who was a finalist in the Telstra awards in 1992, and her niece, Rhonda. Henry learned to carve birds by watching her cousin-brother and Rhonda’s father-in-law, the late Tiwi artist Sebastian Tipiloura.

“He used to make jabirus (storks), pigeons. One day he made kookaburras, one day he made a crow and a kingfisher. I said to Harold, we should do something different, and he said, ‘Why don’t we do cockatoos?’”

The grinder might as well be an extension of Goodman’s right arm. The bird’s head and body emerge from the lower part of the Y. He’s wielding the tool like

a dentist creating the perfect smile. He cuts a diamond shape, outlining its

beak. Suddenly, the bird has a face—and a cheeky smirk. A march fly lands

on Goodman’s back and Henry slaps it away. He just keeps working.

Henry and Goodman are childhood sweethearts; they’ve been a couple

since the mid-1980s. Theirs is an easy relationship filled with banter and mutual respect.

“Harold, he makes them cockatoos really fancy,” she says proudly. “He can make them turning, like a lady cockatoo, like”—Henry turns side-on and cups

a hand behind her ear as if she’s straining to hear a choice piece of gossip—

“or a cockatoo sitting on a tree.”

When titans of business talk about global sales and succession planning, they’re probably not imagining these artists. But Henry and Goodman are conscious of continuing their legacy.

“This thing that we’re doing, we want to pass it on to the next generation,

so we’re teaching Ailena and Felix,” says Henry. “So, our two grandchildren, they’re on their way. Maybe in a couple of years.”

Young Ailena already paints, often joining her grandmother at the painting table outside the shed. And though he’s keen, they think Felix isn’t quite old enough yet to wrangle the grinder.

Powdered with pale sawdust and sitting straight-legged in what now looks like

a small beach, Goodman takes the grinder to the upper arms of the timber Y. “Here comes the feather, the crest.” He splits and shapes them to create four tall curved feathers. It’s clearly a cockatoo—a male, Henry confirms—and, after an hour and a half of grinding and shaping, Goodman’s contribution is complete.

I ask him whether he’s bothered by having an audience. “Nah, I’m just focused,” he says, deadpan. “Plus, I like showing off.”

We walk to the fringes of the billabong. The artists lead us, zigzagging through the trees and tall grass partially gilded by the sun, and we catch glimpses of the water and the lilies growing there. We’d go closer, but our hosts are wary of mosquitos, so we’re not inclined to linger.

Rhonda Henry shows me the ground oven by the billabong where they cook for big family gatherings, sometimes as many as 60 people. “Buffalo, pig, emu, we cook with hot stones. Or we cook fish, and we wrap it in wet paperbark so it doesn’t burn.”

Galah’s photographer Alana Holmberg frames a shot of Henry holding a fallen cockatoo feather, and Goodman does a goofy dance behind her to make Henry laugh.

Goodman tells me later that white cockatoos gather during the day at the top of the water tower next to the shed. “It’s like they’re watching me.”

It’s time to paint the bird. Henry sits outside with her niece and fellow artist Rhonda under a “Welcome birde shop” sign painted by one of the grandchildren, and smooths the timber with fine sandpaper. He’s given a white body and ochre crest, wings finely striped in red and yellow ochre. His beak is grey, his eyes sharp and black.

“The cockatoo has a big role in the traditional way,” explains Henry. “We use the feathers—the ladies use the fine feathers for dilly bags, and ceremony.”

The bird we’ve seen created today is utterly beguiling. Henry and Goodman have turned inanimate timber into something alive, imbued with humour and verve. We know we won’t regret buying him.

Now our cockatoo—we’ve called him Stanley— is on the sideboard, gazing benevolently at all who enter. I like to think of his hundreds of siblings and cousins, maybe perched on a plinth in a New York loft or atop a Parisian shelf, all created with love and a bit of magic by Henry and Goodman in the heart of the Australian bush.

Henry (left) with a fallen cockatoo and (right) finessing her painting. “The cockatoo has a big role in the traditional way,” Henry says. Photographs Alana Holmberg.