Highlighting the work of three remarkable community projects.

Words Megan Holbeck

Galah is highlighting remarkable community work in rural and regional Australia in a series made possible by our partnership with Westfund, a not-for-profit health fund with a 140-year history in regional Australia.

On 19 February 2020, Stacy Jane stayed up all night. She wasn’t out with friends or travelling. Instead she was at a desk in the New South Wales’ Southern Highlands setting up a “very basic” website for Escabags, the charity she launched the following day.

It was the night after Rowan Baxter killed his wife, Hannah Clarke, and their three children in Brisbane, a horrific crime that sparked national outrage and led to the introduction of coercive control laws. It was also the impetus for Jane to start Escabags, a charity that distributes “escape bags” for victims fleeing domestic and family abuse.

Jane says Escabags is designed to bridge the gap “from the moment of escape to the place of safety”. There are two types of bags – for families and individuals – containing toiletries, SIM cards, first-aid kits and children’s comfort items. Each bag holds essential items for the first few days after escape, to avoid the need to return to the family home in the “lethal” period after perpetrators realise they’ve lost control.

During the past five years, 18,000 free bags have been distributed by 2000 stockists across the country, each of whom receives an educational welcome pack and posters for display. Escabags buys most of the items for the bags and relies heavily on volunteer support to pack and distribute; Jane is the only full-time staff member.

Jane tells the story of a couple who regularly used a particular branch of a Bendigo Bank in Western Australia, returning on the same day every week and making the same transactions during every visit. One day the routine changed slightly – the man left the bank and popped into the shop next door. As soon as he left, the woman asked for an escape bag, grabbed it and ran to catch a bus. Says Jane, “She must have looked at our poster every single week and was just waiting for his head to be turned to make that escape.”

Jane is working towards locating an Escabags stockist in every suburb across Australia, from banks and pharmacies to council offices and Optus shops. “They don’t have to be a particular kind of business,” she says, “just a kind one.” As well as meeting the needs of people in crisis, the charity aims to increase awareness of domestic violence and inspire people to be kinder and more empathetic.

Jane’s own life was transformed by the kindness of an Australian family after her violent partner assaulted her on a cruise in New Zealand. The family took her home with them, and later called her daily after she moved back to the UK and into a women’s refuge. Eventually she received a protection visa and relocated to live with them in their home in New South Wales. It was there she started making tote bags as a form of therapy, never imagining what they would become.

The bags hold essential items for the first few days after escape from domestic violence; Escabags founder Stacy Jane; attendees at a corporate volunteer day at Escabags HQ.

After Diane Russell’s son, Jason, committed suicide in 2015, she lost her job, her income and her home. Within a month she found herself in a mental health unit. “It really impacted my life,” she says, in understated summation.

Sixteen months after her son’s death, Russell had recovered sufficiently to reflect, “If this is what it’s done to me, I can only imagine what it’s done to other people.” And in February 2017 she organised the first Hope Walk to raise awareness of suicide and help dispel its stigma.

This was the beginning of the Hawkesbury-based charity Hope4U. Its core mission is to prevent suicide, though a lot of its work is in what Russell calls “post-vention”, supporting families directly after a suicide. The charity helps deal with logistics, from finding alternative accommodation to managing coroner’s reports, funeral arrangements and counselling, while also supporting people to process their grief, acknowledge their feelings, and connect with others.

Russell and her team of trained volunteers work with police, ambulance and other services, as well as responding directly to those who contact them. “For the first six weeks, we just are there for them, [to] listen and support them,” she says.

It’s been a tough time for people living along the Hawkesbury River; the 2019 bushfires were followed by three floods. People are struggling, says Russell, particularly men. After generations of not talking about suicide, she says, “there’s still so much stigma”. By breaking down barriers through conversation, counselling and awareness, Hope4U hopes to encourage people to talk about what has happened and to stop the aftermath of suicide from rippling out to ruin marriages, families and communities. Russell says she doesn’t know of a marriage that has survived the blame that accompanies suicide.

She sees the devastation wreaked by suicide, and has experienced the worst of it herself. After Jason’s death, she struggled with suicidal ideation. Then five years later, her youngest son Aaron killed himself.

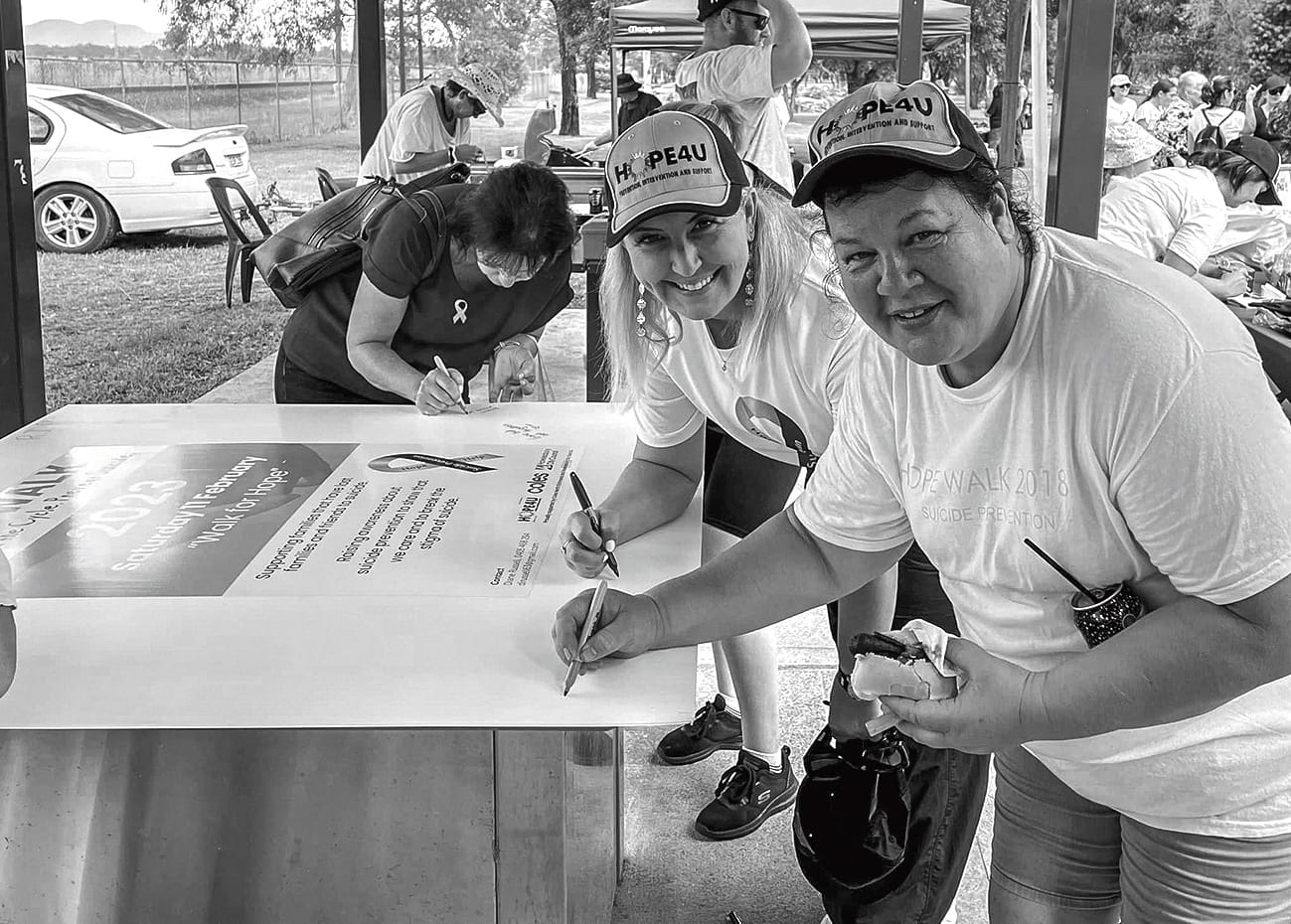

Hope4U partners with organisations across Blacktown, the Nepean, Blue Mountains and Hawkesbury, running men’s support groups, workshops and suicide grief support groups. As well as the annual Hope Walk, the charity helps organise mental health forums and community days, and works with high-risk groups in the area.

Participants in the annual Hope4U Hope Walk.

Every Thursday the Illawarra-based charity Need a Feed puts on a two-course lunch at the Uniting Church in Bulli. Some diners are homeless, some struggle with mental health and addiction. For others this meal is their only social interaction.

New faces are scattered among the regulars. One thing remains the same each week: the warmth of the welcome served along with the meal.

Need a Feed’s purpose goes deeper than the table. It aims to connect with people over food and in the process build a community in which people feel comfortable to access the help they need. As well as distributing monthly food gifts, the charity holds regular events – including lunch on Thursdays and Breakfast Buddies on Mondays establishing the trust necessary to help people when they’re ready.

“You can generally see what people need to do,” says the charity’s founder, Shaz Harrison. “But if they’re not ready, they’re not going to do it. They need to just have someone walk with them along the way.” Need a Feed serves as a connector, facilitator and negotiator with other organisations in the area.

Harrison believes she was meant to look after people. Her mission was spelled out on the sign attached to her cot when her adoptive parents arrived to collect the one-month-old baby. “Feed me,” it read.

She grew up and after selling a business in 2012, she decided to do just that, laying the foundations for Need a Feed by giving 100 food gifts and fresh chicken sandwiches to a neighbourhood centre. The charity has grown exponentially, last year providing 3660 bacon-and-egg rolls, 2780 meals and 750 food gifts.

The charity has launched other projects along the way, including a coffee van in central Wollongong in 2017. It was chaotic in the beginning – on its first day of operation someone was stabbed – but eventually its customers formed a community in which regulars helped with the daily set-up and nearby hairdressers offered free cuts. In 2023 the van was sold and the Breakfast Buddies program was established in the same spot.

Harrison is proud that the charity has created a sense of belonging and transformed lives. Next up, Need a Feed plans to buy a mobile food van and prepare a second weekly breakfast, another chance to cook and connect.

Need a Feed volunteers; Need a Feed’s founder Shaz Harrison and a lunch guest.