Lottie Consalvo and James Drinkwater live, make and collect art in one of the most storied buildings in Newcastle.

Words Kym Elphinstone & Jo Higgins

Photography Dave Wheeler

JAMES Drinkwater was at the pharmacy waiting for a vaccination when he got talking with the person in front of him. “He said, ‘You’re those artists! You should

buy my building!”’

The building was Longworth House, originally known as Wood’s Chambers, designed and built by the German architect Frederick Menkens in 1892 for merchant and brewer Joseph Wood. “They say if you throw a stone in Newcastle, you hit a Menkens building.”

Drinkwater grew up in Newcastle and recalls the mythology surrounding Longworth House. During its lifetime, which has been punctuated by periods of abandonment and dereliction, it was bought by William Longworth, donated to a mysterious patriots society, and used as a function centre and legendary punk venue.

And now, following that serendipitous conversation in the pharmacy, it’s home and studio to “those artists”: Lottie Consalvo and James Drinkwater, and their children, Vinnie and Hester.

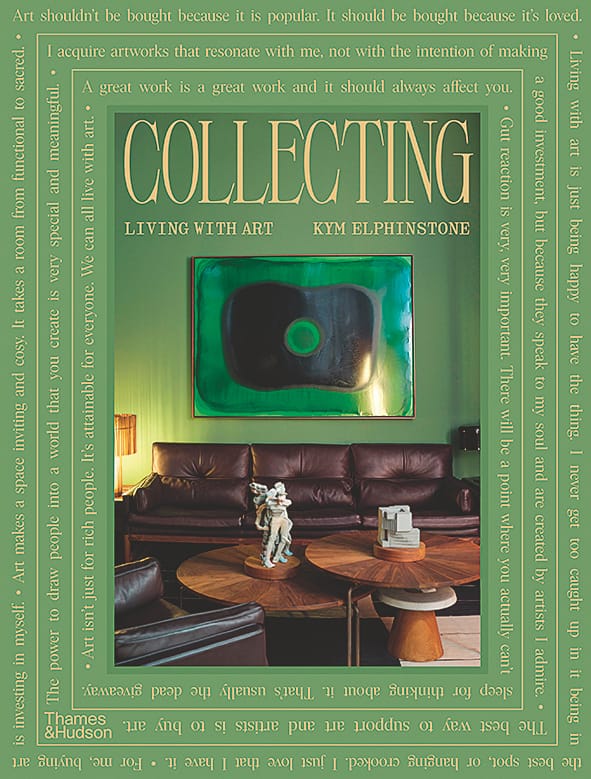

Partially completed sculptures by Consalvo rest in the living room, watched over by a large red painting by Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori; Ceramic plates by Drinkwater. “Art makes a space inviting and cosy. It takes a room from functional to sacred,” says Consalvo. Photography by Dave Wheeler.

“We often say we feel like it was actually built for us,” says Consalvo, who shares a studio with Drinkwater in what was once the upstairs ballroom. With major restoration work undertaken long before they bought it, they realise how lucky they are to be its current custodians. “If we took it on with all those burdens, we probably couldn’t have done it,” says Drinkwater. “But it’s so specific to our requirements as a family, and as practitioners it just suits us to a tee.”

The couple lived in Melbourne and Berlin before settling in Newcastle in 2012. They had been making and collecting art all that time, and moving to Longworth House has finally allowed them to unpack everything. “We’ve always lived in pokey little places. I remember that moment when we both realised that we can actually start to see and celebrate these things – give them breath and space,” says Drinkwater.

Their art collection is an integral part of their lives as artists and includes much-loved swaps with friends. “Because you know how much it’s going to be adored, there’s this nice feeling of knowing that your work is hanging in a space they love, too,” says Consalvo.

Alongside works that have been swapped and acquired, there are also gifts in thanks for their hospitality. Alex Seton’s light pendant and a carved marble axe by Mitch Ferrie, seemingly lobbed into the wall, are legacies of their stay while installing an exhibition at The Lock-Up, a contemporary art space just around the corner.

The kitchen ceiling used to feature a painting by Mason Saltarrelli. “He did it the night before he left, up a ladder with a bottle of tequila,” says Drinkwater. “It gave us this idea of slowly commissioning artists over the next 10 years to paint other sections of the ceiling. Whether or not that happens, all those things are now a possibility.”

In the living-dining room, three large works form visual anchor points. One is a black-and-white photograph, Sleepless, by long-time friend Sarah Mosca. “We just love that work; it holds the whole collection together for us,” says Drinkwater.

The other two are by Consalvo and her father, Dino Consalvo. “My father has been the biggest influence on my trajectory as an artist and he has pushed us the most to commit to our art,” she says. “‘Don’t get scared. Just keep pushing, don’t get distracted, don’t buy into what’s normal.’”

Art brightens the kids’ spaces, including works by Drinkwater (above cupboard) and Alan Jones (left); in their daughter’s room, paintings by Chris Horder (left) and Robert Jacks (right); the couple pause in the light-filled atrium; more works by Drinkwater (left) and Chris Horder (right) hang in a child’s bedroom. Photography by Dave Wheeler.

The couple had other ideas for that spot but when Dino’s artwork went up, they realised it was the only place for it. “It’s a shrine to him in a way, but it’s so nice to have that here to show my lineage. Everyone asks about it.”

Other works, including a small Ramesh Mario Nithiyendran sculpture and a swapped Georgia Spain painting, speak to recurring interests in material messiness and works that fall outside an artist’s usual oeuvre. Other works include swaps with Eleanor Louise Butt and Michael Gearin, and recent purchases by Anabel Robinson and Dean Beletich.

Art can be found everywhere. Early ceramic works by Drinkwater hang in the kitchen, paintings by everyone from Miranda Skoczek and Chris Horder to Turbo Brown, Brad Snape and Alan Jones are in their children’s rooms – chosen by them – while in the front rooms, Raymond Young’s carved shields keep company with a sprawling salon hang that includes work by Sally Gabori and Tony Tuckson.

“Sometimes you position things in the house so you can visit them at certain times of the day. Often it’s a case of, ‘I can’t have that there because I won’t see it all the time,’” says Consalvo.

The works they don’t look at, even when they’re hanging prominently, are their own. “In this house, we’ve been able to put up more of our own work, which we’ve never done before but it’s usually in a spot we’re hoping to fill with another artist’s work. I look at James’s work; I never see mine.”

Their home is also a workplace. If they aren’t hosting collectors or artists, they’re offering the dining room to Newcastle Art Gallery, Newcastle Writers Festival and The Lock-Up for events and local openings. Their investment in the city’s creative community and the possibilities for Longworth House are intrinsic to their understanding of home.

“What I love about living and working in the same space is that there’s no divide between work and life,” says Consalvo. Drinkwater agrees. “Someone asked me how I juggle life and work. For starters, my work is about the theatre of the domestic. The work doesn’t exist without all this.”