Annabelle Hickson, Helen Anderson and Lucy Munro on the best (mostly Australian) books they’ve pulled from the shelf in the past few months.

“This story starts twenty years ago with the birth of my son. When he was only hours old, my mother and my friend whispered their leave and left he and I to learn each other. In the quiet, the spectre of my husband’s death, only ten weeks earlier, hovered over us. I lay in the bed and looked into the dark, and then I turned and looked at my perfect baby.”

These opening lines hit like a punch to the stomach. Yet there is also a feeling of hope; a gradient of emotion that the author explores skilfully in this memoir.

Compiled from lambing diary entries penned during the 2018– 19 drought on her Tasmanian sheep property, Mackellar contemplates the notion of tension—between stubbornness and strength; mothering and being mothered; between intervention and letting nature take its course.

It’s a book that is both about and not about sheep. Mackellar uses the livestock as a conduit to lead the reader through the years to the people, places and animals that have shaped the life she has created and the mother she has become. LM

After decades of suburban life defined by marriage, motherhood, mortgages and work, 62-year-old newspaper journalist Susan Johnson found herself dreaming about leaving Brisbane and returning to the Greek island of Kythera, a place that she “fell fatally and irrevocably in love with” in the 1970s.

Her young adult sons had recently moved overseas and she had taken redundancy at The Courier-Mail. Freedom to return to Greece was within reach. The one catch was her 85-year-old mother. She couldn’t leave Barbara behind in Brisbane. So she asked her to come. Barbara said, “Why not?”

Johnson charts the not-alwaysrosy time she and her mother shared on Kythera, examining their relationship as unflinchingly as she looks at herself.

It’s a travel memoir without a skerrick of sickly sweet, full of complicated, real relationships surrounded by the sparkling azure waters of the Aegean, Cretan and Ionian seas. AH

As bleak as this book sounds, it’s a loving, insightful and at times funny look at the suicidal mind, written by someone who has tried to kill himself more than 10 times.

The journalistic euphemism for death by suicide—“police said there were no suspicious circumstances” —is used for the best of reasons. Research suggests that widely publicised suicides increase the number of other suicide attempts. “But the happy statistical fact,” writes Martin, “is that talking about suicidal thoughts, actual attempts, and the whole painful and embarrassing business tends to discourage the act.”

Martin suggests we don’t speak of suicide honourably because at some level we don’t sympathise with the person who kills themselves. “Perhaps because we all experience suffering in some way ... yet choose to go on living, we judge others who’ve given up on life.” In its attempt to speak sympathetically of people who have killed or tried to kill themselves, this book gives us tools to talk about suicide, and perhaps try to understand it in a dignified way, without the shame of stigma and taboo. AH

This is a tale of monstrous proportions, about a killing machine weighing more than 50 tonnes, as big as a whale, with a bite force 14 times that of a great white shark. While it’s ostensibly about the rise and fall of the giant shark Otodus megalodon, aka Big Meg, this story is as much a tale of obsession, cutting-edge palaeontology and still-living creatures even more terrifying than the long-gone megalodon (consider the zombie-like Greenland shark that lives to 400 and has empty sockets inhabited by eye-eating parasites).

It’s also the story of a boy named Tim whose life changed at 16 when he stumbled across a fossilised megalodon tooth in western Victoria. Flannery’s fascination with the predator propelled not just his own life as a scientist, explorer and conservationist, but that of his daughter and co-author, Emma.

While extinction is forever, writes Flannery senior, “the extinction of the megalodon was not the end of its story”. This is natural history with the phwoar factor. HA

Is there room for two ambitious artists in one relationship? That’s the question posed by Kylie Needham in her debut novel.

The story follows the quiet and unassuming Frances, a painter living a solitary life on Sydney’s outskirts. When she receives an invitation to her ex-lover’s exhibition opening, we are transported back to Frances’ university days and the romance between the ego-driven and desperately insecure artist Clem, and his muse, Frances.

Any thoughts that this is a story you’ve read before are quickly diminished by Needham, whose visual and poetic prose moves seamlessly between timelines and places of fact and fiction. The author captures the friction that exists between an artist and the art world, building to an explosive act of fury that will stay with you long after the last page.

Who and what stands in the way of a woman’s creativity, Needham asks. Is it a husband? Children? Desire? In Frances’ case, it might be all three. LM

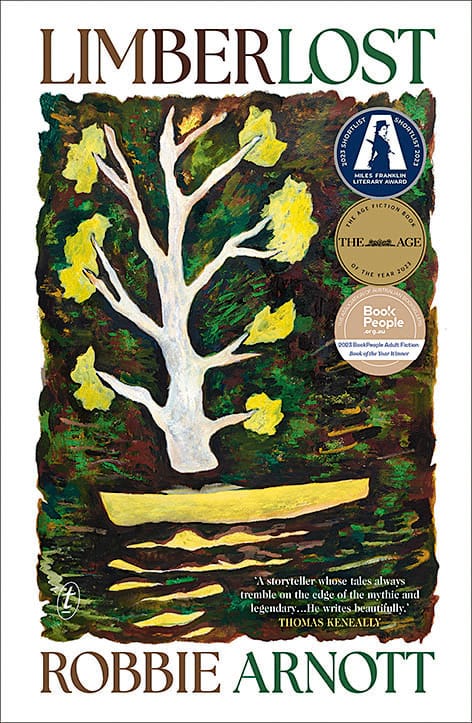

“It was summer, and in the long blond light of the season Ned aimed to kill as many rabbits as he could.” And if he killed enough rabbits, he might earn enough to buy his own boat.

This is the plot summary in a nutshell. It’s modest on the face of it, and yet there’s a world of unspoken family dysfunction and quiet courage hidden in Arnott’s undertaking.

This was the summer that Ned grew up, the summer that defined the course of his long life. Without leaving home, on an apple orchard in northern Tasmania during World War II, the boy comes of age, finding freedom the hard way, a ruined little boat of Huon pine and—a chicken-thieving quoll. Years later, Ned remembers “its fierce presence, filling that summer with a kind of primeval purpose”, a symbol of the dark forces of the forest.

Arnott connects characters with each other and with nature in burnished, spare prose, relying on precision and quietness, rather than showiness or sentiment, to hit its marks. HA