As the global empire of gallerist Michael Reid continues to grow, his country-town ‘art destination’ in the Hunter Valley looms large as the place where he lives and takes risks.

Words Jacqui Taffel

Photography Brigid Arnott

Bunty is not taking no for an answer. Michael Reid keeps pocketing the balls she delivers at our feet, and she keeps looking at us with hopeful border collie eyes. Each time the ball disappears, she’s off to find another. Surely, eventually, one of us will throw it for her.

Dressed in flannel shirt, old jeans and worn RM Williams boots, Reid is sitting under a café umbrella in Murrurundi in the Upper Hunter Valley, surrounded by the gardens and buildings, old and new, he has transformed into a serious art destination on the New England Highway.

One of Australia’s most successful and enduring commercial gallerists and art consultants, Reid is known as an astute, strategic operator. Yet the reasons he chose this small country town – population about 950 – to establish a gallery and, eventually, as a place to live, are as much personal as about business.

Michael Reid Murrurundi is one of five galleries, from Sydney to the New South Wales Southern Highlands to Berlin, that represent Reid’s bricks-and-mortar empire, augmented by online spin-offs including Michael Reid CLAY for ceramic art and Michael Reid LAND selling boutique real estate. He is considering another regional gallery in the Northern Rivers region of New South Wales but his next venture, after years of research and groundwork, is in Los Angeles.

Reid concedes this is not the most opportune moment for a US launch, but playing it safe has never been his forte. He believes decisive leadership is crucial to survive and thrive in the contemporary art world – and business in general – but he’s also happy to be proved decisively wrong, and learn from his decisive mistakes.

“I have surrounded myself with people who will very kindly corral me and control me and help me distil what I’m trying to do,” he says.

Since starting his own art consulting business in 1996, his wins far outnumber the losses. Reid’s bold expansion plans to the US are remarkable given the difficult economic times, when so many significant galleries around Australia have closed in recent years.

He acknowledges the art trade has changed dramatically in the past decade. “No one goes on a Saturday afternoon around 10 galleries anymore,” Reid says. “They look on their iPhone, see 20 galleries, and only go to one. So you’ve got to create a situation that, wherever they’re going, there’s a good reason they have to be there to see it.”

Michael Reid Murrurundi is that kind of experience. An appealing road-trip destination, three-and-a-half hours’ drive north of Sydney, it has changing exhibitions, an expertly curated shop, a lush, cool-climate garden that is spangled in summer with pretty Anatolian hollyhocks, and a café with good soup and serious coffee. “I wouldn’t open another gallery without a coffee shop,” Reid notes. “People can’t be seconds from beverages.”

As well as attracting out-of-towners the place is a local hub, with Saturday morning yoga classes in the gallery, and residents of the town – known by locals as “Murra” – dropping by for caffeine. Reid greets them and their dogs by name.

This chapter of his life began in 2002, when Reid and his wife, Nellie Dawes, bought Bobadil House from her distant relative. The beautiful but decrepit early Victorian-era house was originally the Woolpack Inn, a Cobb & Co stagecoach post built in 1841-42. John Sevil, Dawes’s great-great-great-great grandfather, converted it to a family home in the late 1800s. The property also encompassed a ruined colonial sandstone cellblock-turned-stables, set in a madly overgrown 11-acre garden.

As a seasoned art dealer who learned the ropes at renowned fine-art auction house Christie’s in London, and who before that practised as a criminal lawyer, did he broker a good deal? “We paid the record price for a house in the Upper Hunter Valley,” he replies. “We made it into The Land.”

So, no bargain. Any buyers’ remorse? Oh yes, he says. The grounds were choked with privet and blackberry, which took bulldozers and 80 truckloads to clear. Most rooms in the house had no electricity and the walls had huge cracks from an earthquake here in 1987. “It was a wreck, and still is a wreck. It was a daunting thing to buy.”

The sandstone cellblock, once used to imprison convict road labourers, took two years to clear and rebuild as the first Michael Reid Murrurundi gallery space, which opened in 2007. This became the concept store and kiosk when the larger, custom-built gallery opened in 2018 in the form of a big tin shed.

Reid has plans to turn this second gallery into a restaurant and build a larger one with highway frontage. But first he’s installing an outdoor pizza oven he designed himself. It’s inspired by the old meat safes from his childhood growing up in Narrandera and Wagga Wagga. He envisages visitors eating pizza under one of the industrial steel pergolas he has built, draped with wisteria, passionfruit and grape vines to offer shade in summer’s extreme heat.

The fireplace designed by Reid; inside the gallery; a pergola hung with vines for shade in summer; the former colonial cellblock; now a shop and café; oyster plants (Acanthus mollis) and Anatolian hollyhocks line the pathway. Photography by Brigid Arnott.

“Living in the country is a dream, but you’ve got to actually do stuff,” Reid says. “You can’t just live here and expect to have a wonderful life. So I had to make the industry here for me to enjoy the life that I want.”

This industry has in turn boosted the country town and community, in a valley on the Pages River surrounded by the Liverpool Range, with its distinctive volcanic basalt cliffs and rock formations. Upper Hunter Shire councillor Peter McGill has lived here for five years after moving from Sydney, as Reid did. “The gallery has been a very positive addition,” he says. “Murrurundi has a reputation for being an arty community but a lot of the artists are hidden from view. The gallery opens it up so people can see art from around Australia. It’s been good for the psyche of the town.”

Both Reid and Dawes have strong family connections to this area. Dawes grew up near Willow Tree, the neighbouring town, while Reid’s father grew up in Gundy, near Scone. Reid went to Scone every summer as a child, where his grandmother and aunts lived – two aunts are still there. His father was a farm machinery dealer and his mother was a teacher at country high schools.

“The reality is I love cities, but I wasn’t born in one and I don’t want to die in one,” Reid says.

A work by Davida Allen in the entrance hall of Bobadil House; the back verandah; the summer sitting room, cooled by a cellar below; the house “was a daunting thing to buy”, says Reid. Photography by Brigid Arnott.

After staying in Bobadil House on and off since 2003, he and Dawes moved here as their main residence in 2019, leaving Elizabeth Bay in Sydney. Establishing the property’s business side was Reid’s first priority, but he now finally has DA approval to renovate the old two-storey house.

Walking through it now, he hasn’t exaggerated – the place is a wreck, chilly and derelict. “But it’s dry,” he says. “The roof is iron, not tin – it’s colonial. It won’t rust in another hundred years, and sandstone doesn’t fall down as long as the roof’s fine.”

The entry hallway contains piles of books, paintings large and small, a red vintage child’s car and a life-sized stuffed kangaroo. On closer inspection, Bobadil’s original details emerge: beautifully faded Victorian woven lino; Norfolk Island pine joinery; wooden blinds made by Maitland’s Fry Bros cabinetmakers and undertakers, still in business; and unusual marbleised wood fireplaces, mingled with the couple’s scattered possessions.

In an upstairs room Reid gestures grandly at the disturbing brown stains running down the wall. “This is what I call the Great Possum Pisses of Murrurundi: 160 years of possum piss.”

When they renovate, he says, that wall will stay, complete with well-aged stains. New additions will include a kitchen wing and an old-fashioned sleep-out, open to the elements, for Reid and Dawes’s summer bedroom. There will also finally be an

indoor bathroom. They built an outdoor bathroom behind the house three years ago because a black snake liked to pop up unannounced in the old one.

Still upstairs, we peer out the balcony windows at the rusted lacework and broken floorboards, but go no further. “I can’t take you out there,” he says, “it’s too dangerous.”

Reid’s willingness to live like this is one of his secret weapons in business. “I’m prepared to subjugate or deny material considerations to achieve what I want,” he insists. “I drive a 23-year-old car. I live in an unrenovated house. My life is not materially lush.”

What drives him is the knowledge “that I am better than everyone else at what I choose to be better at”.

It’s hard to argue, given his achievements and portfolio of galleries, each of which he says represents “a different cultural catchment area”.

The main Sydney gallery in Chippendale shows his most established, blue-chip artists. The Berrima gallery caters for the well-heeled Southern Highlands art crowd. Berlin is mainly First Nations art and photography for European collectors. The Northern Beaches space on the outskirts of Sydney shows unrepresented emerging artists. And Murrurundi shows mainly emerging artists from regional areas. Each year Reid uncovers a new crop of promising unrepresented artists from around Australia with the National Emerging Art Prize, which he launched in 2021.

The Murra gallery added an important element to this art ecosystem – Reid could afford to take risks here. “If you’re a major Sydney art gallery paying $250,000 a year rent, you don’t have the capacity financially to show emerging artists, you cannot have a bad month.”

At Murra he can sell work by artists on the way up and develop some to eventually show at his Sydney gallery. “We literally funnel talent through and provide them with a career path, which is rare.”

He believes the regional art scene in Australia is stronger now than it’s ever been, in large part due to the NBN improving communication, which has allowed artists anywhere to participate in the wider art world, national and global. Most artworks sales at Murra are made online, and quite a lot goes overseas. “Many really great Australian artists do not live in urban areas – they don’t want to and they don’t need to.”

He feels there is more regional pride now. “We’re not chippy or yokel. You can see it with the Galah Regional Photography Prize, with extremely good practitioners and images, where 20 years ago that would have been hokey. I also think lots of people in the cities love getting out and going to regional areas.”

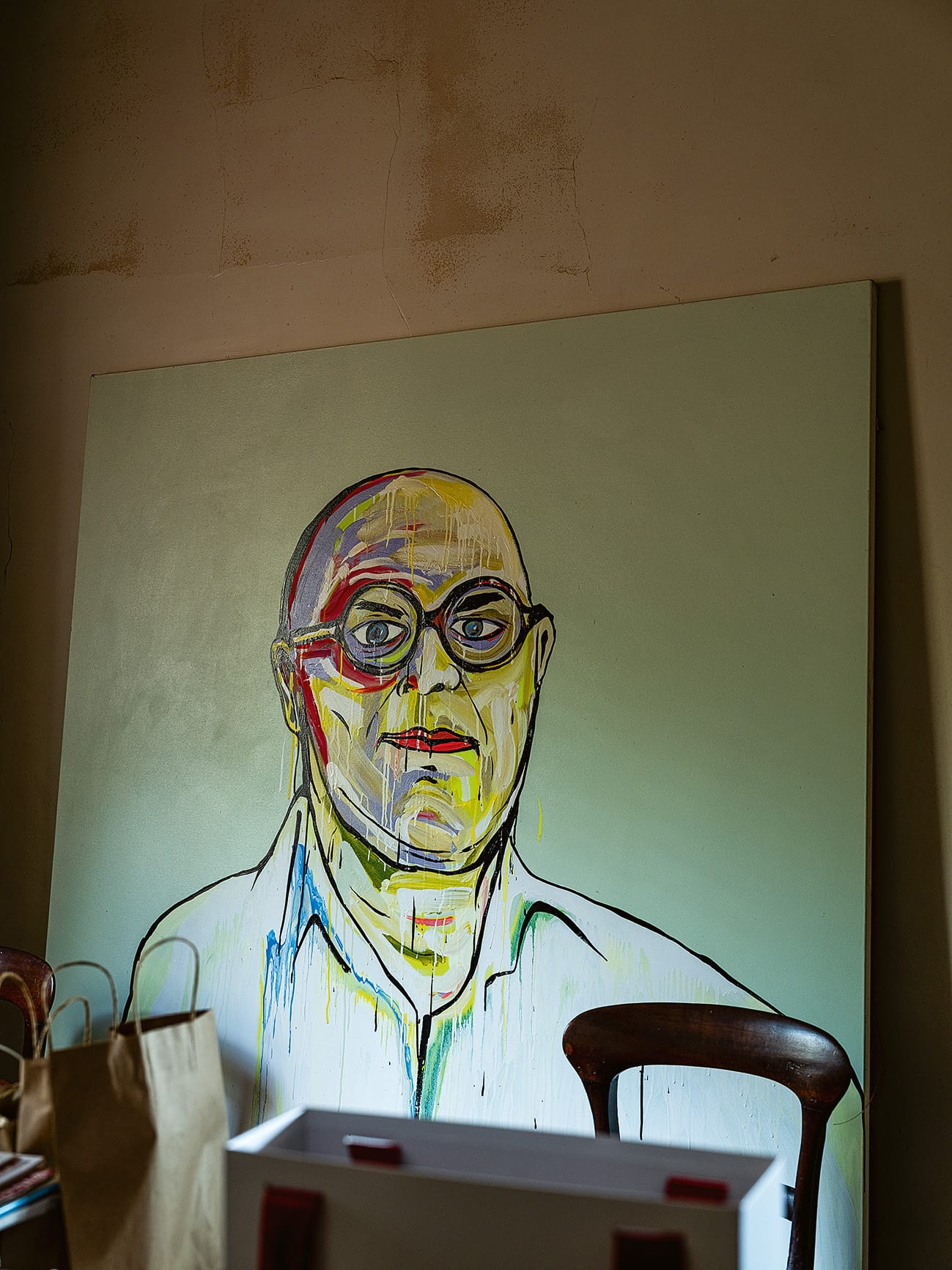

Reid and Bunty in the garden next to the cellblock shop; portraits of Reid by Robert Malherbe (bottom) and Marc Etherington in Bobadil House. Photography by Brigid Arnott.

Walking through the garden, past the avenue of Manchurian pear trees that Reid planted, and past the raised vegie garden beds where he grows garlic and other produce for the cafe, we come across his John Deere mower. He loves to “hoon around” on it but it proved a challenge. His dyslexia, diagnosed as a child, also affects coordination. The tight turns required on the mower were hard to master. “I’m better at it now, but it took me a long time. I ran into a lot of trees.”

A few years ago a gigantic red gum fell over behind the gallery (natural causes, not related to Reid’s driving). In its place he has installed a lily pond in the form of a nine-metre-long concrete trough, flanked by gabion basket stone walls and more lawn to mow.

Reid’s design cues came from Australian garden expert James Broadbent, who pointed out that Bobadil House and similar properties were workplaces, not stately homes. Though the house was grand for its time, it was still based around agricultural industry. “There were horse paddocks and an orchard and vegetable garden and the convict cellblock,” Reid says. “They didn’t mow the lawns, they had sheep.”

Broadbent’s advice was to avoid “tizzying” up the place. Reid describes the results as “rural Bauhaus”, with one of his favourite features being the sculptural cantilevered outdoor fireplace. He designed it himself, with help from architect William Zuccon, who also did the tin shed gallery and house reno plans. Lots of visiting architects have taken photos of the fireplace. “So I’m expecting it to pop up in luxury homes all over the beaches of Australia.”

Reid has never been interested in work-life balance – work is his life. But here in Murrurundi, his work includes growing garlic, mowing, and designing pizza ovens. And, finally, throwing the ball to Bunty.

I wonder, after decades of promoting artists and their work, is all this his own work of art?

“Yes, absolutely!” he replies. “Business for me is a very creative space. I’m only inhibited by capital, and I generate my own. All of my multi-million-dollar business goes back into my multi-million-dollar business. It’s incredibly exciting.”